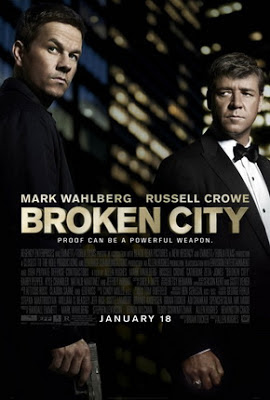

In Broken City (2013) Mark Wahlberg plays an ex-cop named Billy Taggart, who became a private investigator after being let go from the force. He shot and killed a young man, allegedly in self-defense, and the incident aroused a considerable amount of media attention and public indignation. Seven years later, Billy is hired by Nick Hostetler, the mayor of New York (Russell Crowe), to spy on the mayor's philandering wife (Catherine Zeta-Jones). But Billy soon discovers that he's embroiled in something much deeper and more dangerous than mere adultery.

The elements of Broken City could almost have been fashioned into a film noir thriller from the 1940s. It has all kinds of bad, corrupt people and some light scandalous touches. But that's where the similarities between that genre and this crime mishmash end. The film never comes together, never becomes exciting, must-see-this-to-the-end movie-watching. Mark Wahlberg is a capable actor, but in Broken City his Billy Taggart has very little credibility. He's not compelling enough to be the kind of character who's inexplicably driven, the way Philip Marlowe was in The Long Goodbye, to figure out the mystery, despite his increasing irrelevance to the investigation.

Billy Taggart keeps showing up where he seems totally out of place: at crime scene investigations in which he shouldn't be allowed, at expensive political cocktail parties where his presence gives him away. The movie doesn't make much use of these incredulous moments. Billy's just there, conveniently invited into important scenes for the sake of the plot. There's also a scene where Billy discovers some important documents--freshly hurled into a dumpster--that help reveal the mayor's political maneuverings. Why, you ask, wasn't this shredded? Especially when, seconds later, Billy peers into a window only to see more compromising documents being destroyed the way you'd expect them to.

The supporting cast is a good cast, but is given very little to do, with the exception of Russell Crowe. He's always been very good at being very bad, and in Broken City he captures the essence of the charming, corrupt political animal, talking his way out of trouble and into the people's hearts. As his wife, Catherine Zeta-Jones looks like a strong, civically involved first lady of NYC, but the script doesn't give her much to do. It's a problem I keep noticing for actresses. They seem to exist in movies to serve a function, rather than to interpret and illuminate a character or entertain us with their own considerable acting talents. It's the men who get to have all the fun. Zeta-Jones has a few little quips here and there, but she's really just eye candy for the sympathetic observer. And Kyle Chandler, as the man she's supposedly sleeping with, who just happens to be the campaign adviser to the mayor's opponent, doesn't have much chance to shine either.

The subplot, involving Billy's actress-wife Natalie (Natalie Martinez), nearly sinks the movie. She's premiering in an "indie film" (the phrase is uttered with such limited understanding that it's difficult to believe she's an actor, or that the screenwriter knows much about movies), and the tacit tension between Billy and Natalie becomes palpable at the premiere, during the movie's explicit love scene, between Natalie and her male co-star. Billy's rage turns to boozing, and their relationship goes on the rocks with the drinks. It's bad. Natalie's movie is called Kiss of Life, and the opening credits are featured over an ocean shore on a hazy day. The conversation leading up to the sex scene is laughable: shallow twaddle about the meaning of life, or something pseudo-deep, as I remember it. It's such a preposterous and uninteresting subplot that even the writer abandons it after a while. Natalie leaves and she isn't mentioned again.

One redeeming quality: the chummy relationship between Billy and his assistant, Katy (Alona Tal), is amusing and the only fun aspect of this movie. (Except, their comic banter starts to remind you of crime shows like NCIS, which is never a good sign for a movie.) With Jeffrey Wright, Barry Pepper (playing the mayor's opponent), Michael Beach, and James Ransone. Directed by Allan Hughes. 109 min. Watch The Big Sleep instead. Or The Long Goodbye. ★½