In Metropolitan (1990), Tom Townsend, who's just finished his first semester at Princeton, unexpectedly enters into the inner-circle of a group of upper-class New York college students during debutante season. It's like a preppie Breakfast Club only everyone's too intellectual to wallow in self-pity. Most of the action takes place in one of the adolescent's homes, where the group stays up late into the night drinking, talking, and occasionally playing Bridge or some other game. They're socialites in training. It would be pretentious if it wasn't so funny and so earnest.

The writer-director Whit Stillman pulls off something impressive: he creates a believable, sympathetic, even inviting, world comprised of somewhat stuck-up, educated young people who are endearing in spite of themselves. They talk about philosophy and economics but they also gossip, and they're acutely aware of their social world. They're also naive, but in their precocious over-analyzing they manage to find at least some degree of acceptance that, though they think they know everything, they may also be wrong about some things.

The performances by the fresh-faced cast are mostly good. This is an extremely talky movie, one that almost plays like a filmed stage production. It's a movie about ideas and social relationships, and while Stillman isn't totally ignorant of or indifferent to the cinematic elements of his movie, he's far more attuned to the dialogic aspects. We're immersed in this inner-circle like a fly on the wall as the social dramas play out: the scathing remarks, the incisive criticisms, the hopeful longings for romance and success, the cynical worries of the future: it's all wrapped up in a peculiar fabric of conversation. You're never even sure how much these people like each other.

At times they seem to have cut each other to pieces, and then moments later it's as though nothing's happened, and they're chasing after some other thread of conversation. It's a fascinating movie; not perfect, but never boring, and totally unpredictable. I was charmed by it in a way I haven't been in a long time.

The cast includes: Edward Clements as Tom, the newcomer who has a lot of "big" ideas about economics, culture, and philosophy, but is also still a little gauche when it comes to girls; Carolyn Farina as Audrey, the bookish girl who's never really been in love before; Chris Eigeman (a stand-out performance), as Nick, the guy who pisses everyone off with his cynical honesty and harsh criticisms of one and all, but is also somehow likable in spite of himself; Taylor Nichols (who made me think of Crispin Glover) as Charlie, the nerdy ideologue who's in love with Audrey but can't get up the nerve to tell her, and resents Tom because Audrey has a crush on him; and Allison Parisi (who, with her raven-like hair and confident, imposing features resembles a young Kirstie Alley), the most "grown-up" acting of the girls; she exudes maternal qualities but is indifferent toward the other girls at the same time. Also starring: Isabel Gillies, Bryan Leder, Will Kempe, and Ellia Thompson. The film was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. 98 min. ★★★½

November 24, 2012

November 23, 2012

The Deep Blue Sea

Originally, The Deep Blue Sea was a play by the English writer Terence Ratigan. It was first adapted to the screen in 1955, with Vivien Leigh in the lead role of Hester, the woman whose feelings about love and desire are too complex for her to put into words. Now Hester is played by Rachel Weisz, whose performance is heartfelt and passionate, even if the movie is a dismal affair. It's all very English, and very grimly heart-wrenching, yet there's a sort of subdued wistfulness about it that keeps it from being histrionic.

When Hester falls in love with a dashing war veteran (the movie is set in London in 1950), she leaves her well-to-do husband William (Simon Russell Beale), a successful judge who's still far too attached to his stultifyingly correct mother (Barbara Jefford). There's a deliciously acidic exchange between Hester and her mother-in-law early in the film, when they're having dinner together with William. The mother-in-law, intent on unmasking Hester's unfitness for her darling son, asks Hester if she plays sports. Hester replies that she's never been very passionate about sports, and then the mother, with sheer, venomous perfection, says, "Beware of passion. It always leads to something ugly...A guarded enthusiasm is much safer." What a wonderful line! And a wonderful exchange.

It would seem that Mum's words were indeed prophetic. Hester's relationship with her new lover, Freddie (he's played by Tom Hiddleston), dissolves almost as quickly as it begins. Strangely enough, her encounters with her husband, who was initially (and understandably) furious with her for having an affair, become more civilized. He seems genuinely concerned about her well-being. But it's never clear if this concern is merely a ruse to win her back. The scandal of an unfaithful wife is bad enough, let alone the shame of a divorce.

This is the kind of film that would have been a lot more earth-shattering in the 1950s. And indeed, the play was, upon its initial debut in 1952, considered an important commentary on the state of relationships between people, post-war. We like to imagine that things (society, people, relationships) had become far more complex. (Were they ever not?) And this piece of British domestic discord is a sort of civilized descent into a private British hell: the hell reserved for the overly passionate. (Perhaps this is the ultimate English fear. I think the mother must have seen it all coming well before even the girl did.)

The movie left me feeling numb. There's nothing new here, nothing being said that hasn't been said before. The question lingers: why did the director, Terence Davies (who adapted the play, presumably so that it would be less stagy), feel so compelled to make this movie now? Perhaps it's a reminder that sixty years of time and progress and technological achievement haven't ceased to clarify much of anything. And perhaps nothing new needs to be said, as the old problems continue to require reflection. The Deep Blue Sea reminds us of the limits of language, and the seemingly inexhaustible depths to which humans will go to hold onto something--or someone--they love, even in the midst of great pain and turmoil.

Probably the most memorable sequence is Hester's flashback of London during the war. Her mind drifts back to that powerful, frightening memory: hiding inside the relative safety of the train station during the London air raids. A man's voice sings the Irish folk song "Molly Malone." It's a lovely, heartbreaking moment. As I reflect on this film, it strikes me that we don't have movies of this kind often enough. The Deep Blue Sea will likely be ignored by the big awards-purveyors because it's not commercial. It doesn't have the slickness we've come to expect in movies today. That's probably why I felt a little bored during it. But we need to applaud filmmakers and actors who take on projects like this: projects that seek to explore the things for which we fail to explain in words; the things which often defy logic. ★★★

When Hester falls in love with a dashing war veteran (the movie is set in London in 1950), she leaves her well-to-do husband William (Simon Russell Beale), a successful judge who's still far too attached to his stultifyingly correct mother (Barbara Jefford). There's a deliciously acidic exchange between Hester and her mother-in-law early in the film, when they're having dinner together with William. The mother-in-law, intent on unmasking Hester's unfitness for her darling son, asks Hester if she plays sports. Hester replies that she's never been very passionate about sports, and then the mother, with sheer, venomous perfection, says, "Beware of passion. It always leads to something ugly...A guarded enthusiasm is much safer." What a wonderful line! And a wonderful exchange.

It would seem that Mum's words were indeed prophetic. Hester's relationship with her new lover, Freddie (he's played by Tom Hiddleston), dissolves almost as quickly as it begins. Strangely enough, her encounters with her husband, who was initially (and understandably) furious with her for having an affair, become more civilized. He seems genuinely concerned about her well-being. But it's never clear if this concern is merely a ruse to win her back. The scandal of an unfaithful wife is bad enough, let alone the shame of a divorce.

This is the kind of film that would have been a lot more earth-shattering in the 1950s. And indeed, the play was, upon its initial debut in 1952, considered an important commentary on the state of relationships between people, post-war. We like to imagine that things (society, people, relationships) had become far more complex. (Were they ever not?) And this piece of British domestic discord is a sort of civilized descent into a private British hell: the hell reserved for the overly passionate. (Perhaps this is the ultimate English fear. I think the mother must have seen it all coming well before even the girl did.)

The movie left me feeling numb. There's nothing new here, nothing being said that hasn't been said before. The question lingers: why did the director, Terence Davies (who adapted the play, presumably so that it would be less stagy), feel so compelled to make this movie now? Perhaps it's a reminder that sixty years of time and progress and technological achievement haven't ceased to clarify much of anything. And perhaps nothing new needs to be said, as the old problems continue to require reflection. The Deep Blue Sea reminds us of the limits of language, and the seemingly inexhaustible depths to which humans will go to hold onto something--or someone--they love, even in the midst of great pain and turmoil.

Probably the most memorable sequence is Hester's flashback of London during the war. Her mind drifts back to that powerful, frightening memory: hiding inside the relative safety of the train station during the London air raids. A man's voice sings the Irish folk song "Molly Malone." It's a lovely, heartbreaking moment. As I reflect on this film, it strikes me that we don't have movies of this kind often enough. The Deep Blue Sea will likely be ignored by the big awards-purveyors because it's not commercial. It doesn't have the slickness we've come to expect in movies today. That's probably why I felt a little bored during it. But we need to applaud filmmakers and actors who take on projects like this: projects that seek to explore the things for which we fail to explain in words; the things which often defy logic. ★★★

Out of Sight

Out of Sight (1998) is a crime comedy that's intermittently clever and dumb. It's got George Clooney, though, as a bank robber who's tired of prison and ready to retire, if he can make a final score that's large enough to sustain him. Director Steven Soderbergh demonstrates his ability to make fun movies here: it's sort of a breezier, less show-offy version of a Tarantino movie, with an interest in developing a relatively straightforward --but layered-- story, rather than twisting it like a pretzel. I'm not so much criticizing Tarantino's movies as noting the difference between this film and say, Jackie Brown (both movies, incidentally, come from novels by Elmore Leonard). Out of Sight is content to be entertaining without being overly clever. Soderbergh is a more conventional director than Tarantino, you might say. He knows how to transcend conventional movies and turn them into something fun and unique, and that's largely what he does with Out of Sight. It has so many funny, quirky moments that are fresh and interesting, and yet it never feels like something so disdainfully self-aware as a Tarantino film.

There are moments when you wonder if the screenwriter, Scott Frank, wasn't paying attention to his material closely enough. He lets characters do things that seem illogical, even stupid, for the sake of advancing the plot in a certain direction. The movie is almost gleefully disinterested in being realistic. You admire its casualness. Clooney has that sort of casual charm to him, and he's perfect for this movie. Jennifer Lopez, as the marshal who falls in love with him, isn't a great actress, but she does have a sense of comic timing, and she's a great beauty too. Her character downplays her obsession with "bad guys," even though she must know she's lying to herself the way the movie is lying to itself, playfully. This heist-farce was made purely for entertainment. But it has enough smarts not to be totally mindless, too.

The supporting cast is a dream: Ving Rhames as Clooney's partner in crime, a tough, weathered criminal who nevertheless confesses his crimes--sometimes prior to committing them--to his ultra-religious sister, a bookkeeper for a televangelist; Don Cheadle as a fellow criminal, who agrees to join forces with Clooney and Rhames to break into the safe of a Detroit millionaire, played by Albert Brooks, who did time with them in Florida (presumably for embezzlement); Dennis Farina as Lopez's father, also in the business; Catherine Keener as one of Clooney's friends in the outside world: a former magician's assistant. She figures in a very amusing scene in which an escaped criminal, played by Luis Guzman, comes to her door to kill her, unaware that Lopez is already there questioning her about Clooney's whereabouts. Keener is another actress with a remarkable comic sensibility: she's subtle, too, never forcing herself on the camera or the audience. She lets her character's intelligence sink in gradually; Steve Zahn plays a moronic stoner who comes to Clooney's assistance (sort of), half-heartedly, and gives away more than he realizes whenever he encounters Lopez, who knows how to work him; Viola Davis as Cheadle's girlfriend; Michael Keaton as Lopez's married lover, an FBI agent who has a great scene with Farina in which he sneakily calls him out on his behavior; Nancy Allen, as Brooks' girlfriend; and, in a cameo appearance at the end, Samuel L. Jackson, as another convict.

There are moments when you wonder if the screenwriter, Scott Frank, wasn't paying attention to his material closely enough. He lets characters do things that seem illogical, even stupid, for the sake of advancing the plot in a certain direction. The movie is almost gleefully disinterested in being realistic. You admire its casualness. Clooney has that sort of casual charm to him, and he's perfect for this movie. Jennifer Lopez, as the marshal who falls in love with him, isn't a great actress, but she does have a sense of comic timing, and she's a great beauty too. Her character downplays her obsession with "bad guys," even though she must know she's lying to herself the way the movie is lying to itself, playfully. This heist-farce was made purely for entertainment. But it has enough smarts not to be totally mindless, too.

The supporting cast is a dream: Ving Rhames as Clooney's partner in crime, a tough, weathered criminal who nevertheless confesses his crimes--sometimes prior to committing them--to his ultra-religious sister, a bookkeeper for a televangelist; Don Cheadle as a fellow criminal, who agrees to join forces with Clooney and Rhames to break into the safe of a Detroit millionaire, played by Albert Brooks, who did time with them in Florida (presumably for embezzlement); Dennis Farina as Lopez's father, also in the business; Catherine Keener as one of Clooney's friends in the outside world: a former magician's assistant. She figures in a very amusing scene in which an escaped criminal, played by Luis Guzman, comes to her door to kill her, unaware that Lopez is already there questioning her about Clooney's whereabouts. Keener is another actress with a remarkable comic sensibility: she's subtle, too, never forcing herself on the camera or the audience. She lets her character's intelligence sink in gradually; Steve Zahn plays a moronic stoner who comes to Clooney's assistance (sort of), half-heartedly, and gives away more than he realizes whenever he encounters Lopez, who knows how to work him; Viola Davis as Cheadle's girlfriend; Michael Keaton as Lopez's married lover, an FBI agent who has a great scene with Farina in which he sneakily calls him out on his behavior; Nancy Allen, as Brooks' girlfriend; and, in a cameo appearance at the end, Samuel L. Jackson, as another convict.

Tags

1998,

Catherine Keener,

Dennis Farina,

Don Cheadle,

George Clooney,

Jennifer Lopez,

Michael Keaton,

Nancy Allen,

Samuel L. Jackson,

Steve Zahn,

Steven Soderbergh,

Ving Rhames,

Viola Davis

November 21, 2012

Kiss Kiss Bang Bang

Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2005) is a movie that tries too hard to be clever. The script, by director Shane Black, is hack work trying to pass itself off as hip, post-modern, meta-noir. That's a lofty goal, considering this is supposed to be a tribute to pulpy crime novels and film noir. It's too carefully self-aware to work. (Black borrowed the title from a 1966 Italian spy movie, as did film critic Pauline Kael, for her second book of movie criticism. Kael observed that those words aptly described the appeal of movies, in a nutshell.)

It's not that Kiss Kiss Bang Bang doesn't have appeal. Robert Downey, Jr. and Val Kilmer are both fun performers, and they're well-paired: Downey plays an up-and-coming actor who's shadowing Kilmer, a gay private eye, so he can be better prepared for a movie role. Downey also narrates, and periodically his narration makes little ironic commentary that's supposed to make light of bad or unclear plot progressions. But instead it just feels like the work of an amateur. And the over-complicated plot, which is supposed to be an homage, feels thoroughly disengaging and disconcertingly practical. Every action seems to be a vehicle for a bad joke. (There's even a character whose name is Flicka, purely so someone can reference her as "my friend Flicka." If that's Shane Black's idea of being clever, I'm out.)

The characters vacillate between participating in the contrived murder plot, and commenting on it with facetious omnipotence. It feels like a cop-out. With Michelle Monaghan, Corbin Bernsen, and Larry Miller. 103 mins.

It's not that Kiss Kiss Bang Bang doesn't have appeal. Robert Downey, Jr. and Val Kilmer are both fun performers, and they're well-paired: Downey plays an up-and-coming actor who's shadowing Kilmer, a gay private eye, so he can be better prepared for a movie role. Downey also narrates, and periodically his narration makes little ironic commentary that's supposed to make light of bad or unclear plot progressions. But instead it just feels like the work of an amateur. And the over-complicated plot, which is supposed to be an homage, feels thoroughly disengaging and disconcertingly practical. Every action seems to be a vehicle for a bad joke. (There's even a character whose name is Flicka, purely so someone can reference her as "my friend Flicka." If that's Shane Black's idea of being clever, I'm out.)

The characters vacillate between participating in the contrived murder plot, and commenting on it with facetious omnipotence. It feels like a cop-out. With Michelle Monaghan, Corbin Bernsen, and Larry Miller. 103 mins.

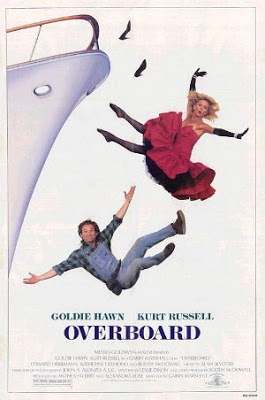

Overboard

I grew up on Goldie Hawn. Overboard (1987) isn't one of her strongest vehicles, but her performance is enjoyable nonetheless. She plays a spoiled millionaire who hires a carpenter (Goldie's real-life significant other, Kurt Russell) to remodel the bedroom closet on her yacht while the boat is docked on the coast of Oregon, awaiting engine repairs. Unhappy with the local carpenter's final product, she pushes him off the boat and into the sea. Later that night, she falls into the ocean herself (unbeknownst to her husband or any of the crew), losing her memory in the process. She's eventually picked up by another boat and taken into town for medical treatment. But when her husband decides not to claim her (she's too much of a bitch even for him), the carpenter sees an opportunity for revenge. He pretends to be her husband, and takes her home to his ramshackle house and four unruly sons, turning her into the homemaker she never was.

You will enjoy Overboard more if you can ignore some of the gaping holes in the plot. (How did he convince the hospital staff he was her husband without a shred of documentary proof?) Goldie's transformation from a bored, boring, bossy snob to a person who actually knows a hard day's work, is fun to watch, especially because she does it with such charm, and she and Kurt Russell have such chemistry.

The movie is overly sentimental and lacks any kind of dependable smartness. It's funniest when the actors have little one-liners, delivered almost under their breath, showing you that the writer, Leslie Dixon, and the director, Garry Marshall, are capable of more than formula movies when given the right material, the right ideas, and the right stars. The stars are right, but the ideas aren't clever enough to make Overboard a complete success as a comedy, even though it is funny. (It's certainly not as embarrassing as it could have been; but it's also not as intelligent or as inventive either.) Most of those 80s comedies I grew up on work because of the performances, not because of the writing or the plot. It's when you remove your focus from the acting and pay attention to the silly, obvious plot that you start finding things to quibble with.

With Roddy McDowall, Edward Herrmann, Katherine Helmond, and Michael Hagerty. 112 mins.

You will enjoy Overboard more if you can ignore some of the gaping holes in the plot. (How did he convince the hospital staff he was her husband without a shred of documentary proof?) Goldie's transformation from a bored, boring, bossy snob to a person who actually knows a hard day's work, is fun to watch, especially because she does it with such charm, and she and Kurt Russell have such chemistry.

The movie is overly sentimental and lacks any kind of dependable smartness. It's funniest when the actors have little one-liners, delivered almost under their breath, showing you that the writer, Leslie Dixon, and the director, Garry Marshall, are capable of more than formula movies when given the right material, the right ideas, and the right stars. The stars are right, but the ideas aren't clever enough to make Overboard a complete success as a comedy, even though it is funny. (It's certainly not as embarrassing as it could have been; but it's also not as intelligent or as inventive either.) Most of those 80s comedies I grew up on work because of the performances, not because of the writing or the plot. It's when you remove your focus from the acting and pay attention to the silly, obvious plot that you start finding things to quibble with.

With Roddy McDowall, Edward Herrmann, Katherine Helmond, and Michael Hagerty. 112 mins.

November 20, 2012

Skyfall

I groaned inwardly at the beginning of the latest Bond picture, Skyfall: Yet another mindless chase scene where rich people in business suits and fancy cars destroy an entire district of middle and lower class people trying to sell fruits and vegetables. Happily, the rest of the movie eschews that drawn-out bit of chaotic action bosh in favor of a more elegant kind of spy thriller. Surely the James Bond movies have become less-Bond-more-Bourne in the last six years (a disappointing evolution, or devolution, actually). Casino Royale was an exciting debut for Daniel Craig as 007, but the movie was overlong and sloppy at times when it should have been taut. Quantum of Solace was mercifully shorter, and entertaining, but slight, unimpressive and far too Bourne-ish to feel like a real Bond installment.

Skyfall unites these two warring aspects of the Bond franchise: it's sort of a return, sort of a departure. Some may have found such ambiguity frustrating. (It's understandable.) But I enjoyed myself through to the ridiculous finale, which, as a friend pointed out, was lifted from the Home Alone playbook. It gets a little bit more personal, although one of the things that has made the Bond movies entertaining is their lack of a sense of tangible reality. They were never particularly rooted in time, except when it came to the technology and the villains, who always reflect real-life political anxieties. Here, the threat is terrorism but more specifically cyber-terrorism, and the villain is Javier Bardem, who's good in a cheap sort of way: he's just a tamer version of the psychopath he played in No Country For Old Men, and a more predictable version of the Joker in The Dark Knight. Bardem needs to play a dad in a Disney movie next if he's going to surprise us ever again. But that won't be a very good surprise.

Judi Dench, as M, gets more story time in Skyfall. M's showing her age, and her ability to lead such an important--or at least, established--wing of British intelligence comes into question after some bad judgment calls. It's always fun to see Judi Dench stand firm and icy like the Queen Mother, which she's sort of becoming. At least, the Queen Mother of British movies. (Sorry Maggie, Helen.) Ralph Fiennes steps in as another Bond boss, Mallory, who's going to oversee M's "voluntary" retirement in a few months. Not to be bested, M throws the British PM the finger with regal precision, determined to see her latest job to the end, whatever that may be.

The director, Sam Mendes, does a good job capturing the visual opulence of the various locations, from Shanghai to rural Scotland. Shanghai comes to life in Skyfall, a neon palace full of dancing lights and eye-popping skyscrapers. It's also the scene of a particularly entertaining--because it's relatively subtle and quiet--confrontation between Bond and a hitman, whom he follows up to the top of one of the skyscrapers by grabbing onto the bottom of the elevator. The finale, which takes place at Bond's childhood home in Scotland--and features an enjoyable performance by Albert Finney as the grizzled caretaker of the place--isn't all that smart, but it's enjoyable anyway.

I also really enjoyed the performance of Naomie Harris, an agent who engages in some amusing banter with James. She's game for anything, and invests her scenes with a sense of fun. Daniel Craig is his usual stoic self, but slightly more vulnerable and bruised up. He remains one of the franchise's best incarnations by not giving too much or too little.

With Berenice Marlohe, Ben Whishaw as a Harry Potterish Q, Helen McCrory, Rory Kinnear, and Ola Rapace. Written by Neal Purvis, Robert Wade, and John Logan. 143 min. ★★★½

Skyfall unites these two warring aspects of the Bond franchise: it's sort of a return, sort of a departure. Some may have found such ambiguity frustrating. (It's understandable.) But I enjoyed myself through to the ridiculous finale, which, as a friend pointed out, was lifted from the Home Alone playbook. It gets a little bit more personal, although one of the things that has made the Bond movies entertaining is their lack of a sense of tangible reality. They were never particularly rooted in time, except when it came to the technology and the villains, who always reflect real-life political anxieties. Here, the threat is terrorism but more specifically cyber-terrorism, and the villain is Javier Bardem, who's good in a cheap sort of way: he's just a tamer version of the psychopath he played in No Country For Old Men, and a more predictable version of the Joker in The Dark Knight. Bardem needs to play a dad in a Disney movie next if he's going to surprise us ever again. But that won't be a very good surprise.

Judi Dench, as M, gets more story time in Skyfall. M's showing her age, and her ability to lead such an important--or at least, established--wing of British intelligence comes into question after some bad judgment calls. It's always fun to see Judi Dench stand firm and icy like the Queen Mother, which she's sort of becoming. At least, the Queen Mother of British movies. (Sorry Maggie, Helen.) Ralph Fiennes steps in as another Bond boss, Mallory, who's going to oversee M's "voluntary" retirement in a few months. Not to be bested, M throws the British PM the finger with regal precision, determined to see her latest job to the end, whatever that may be.

The director, Sam Mendes, does a good job capturing the visual opulence of the various locations, from Shanghai to rural Scotland. Shanghai comes to life in Skyfall, a neon palace full of dancing lights and eye-popping skyscrapers. It's also the scene of a particularly entertaining--because it's relatively subtle and quiet--confrontation between Bond and a hitman, whom he follows up to the top of one of the skyscrapers by grabbing onto the bottom of the elevator. The finale, which takes place at Bond's childhood home in Scotland--and features an enjoyable performance by Albert Finney as the grizzled caretaker of the place--isn't all that smart, but it's enjoyable anyway.

I also really enjoyed the performance of Naomie Harris, an agent who engages in some amusing banter with James. She's game for anything, and invests her scenes with a sense of fun. Daniel Craig is his usual stoic self, but slightly more vulnerable and bruised up. He remains one of the franchise's best incarnations by not giving too much or too little.

With Berenice Marlohe, Ben Whishaw as a Harry Potterish Q, Helen McCrory, Rory Kinnear, and Ola Rapace. Written by Neal Purvis, Robert Wade, and John Logan. 143 min. ★★★½

Night of the Living Dead

This 1990 remake of the George Romero cult classic isn't different enough to justify its existence, or bone-chilling enough to rival the original. But the dedicated will likely find things to enjoy in it. Tony Todd, as Ben (who was the strongest and subtlest character in the 1968 Night), is well-cast, and Patricia Tallman makes a convincing 90's Barbara: she inexplicably transforms from a mousy, wimpy schoolmarm-type to a hybrid of Sigourney Weaver from Alien and Sarah, the lead character from Romero's Day of the Dead. (She overacts as the wimpy Barbara, but she's fun to root for when she turns tough.)

Romero wrote the screenplay, which seems silly as this update isn't fresh enough to conjure up any comparison the way you can with, say, the Siegel and Kaufman versions of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956 and 1978 respectively). With the Night remake, Romero's intent was to try and recoup the money he didn't make from the 1968 film. While the movie was a big hit eventually, Romero and company never saw any of the box office earnings, partly because they failed to copyright the film under its hastily-changed title (it was original called Night of the Flesheaters). But Romero had already made three zombie films, and by now his career had mostly petered out with a number of disappointing releases (including the third zombie flick, Day of the Dead, and 1988's Monkey Shines).

Romero turned the directing duties over to longtime collaborator Tom Savini (the make-up effects guy from Martin, Dawn of the Dead, Day of the Dead, and a number of non-Romero films including Friday the 13th). Savini doesn't do an embarrassing job, but he's too much of a novice to salvage the material from being just so-so. As a make-up artist, Savini's instincts are garishly disgusting and funny. As a director he seems too careful to invest any of that eccentric monster magic into the movie.

With Tom Towles, McKee Anderson, William Butler, Kate Finneran, and Bill Moseley. 88 mins.

Romero wrote the screenplay, which seems silly as this update isn't fresh enough to conjure up any comparison the way you can with, say, the Siegel and Kaufman versions of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956 and 1978 respectively). With the Night remake, Romero's intent was to try and recoup the money he didn't make from the 1968 film. While the movie was a big hit eventually, Romero and company never saw any of the box office earnings, partly because they failed to copyright the film under its hastily-changed title (it was original called Night of the Flesheaters). But Romero had already made three zombie films, and by now his career had mostly petered out with a number of disappointing releases (including the third zombie flick, Day of the Dead, and 1988's Monkey Shines).

Romero turned the directing duties over to longtime collaborator Tom Savini (the make-up effects guy from Martin, Dawn of the Dead, Day of the Dead, and a number of non-Romero films including Friday the 13th). Savini doesn't do an embarrassing job, but he's too much of a novice to salvage the material from being just so-so. As a make-up artist, Savini's instincts are garishly disgusting and funny. As a director he seems too careful to invest any of that eccentric monster magic into the movie.

With Tom Towles, McKee Anderson, William Butler, Kate Finneran, and Bill Moseley. 88 mins.

November 19, 2012

Holy Motors

In one such appointment, he dons yellow, ghastly-looking fingernails, stringy red hair, and an ugly green suit, and becomes a shambling, semi-mentally-retarded troll. He wanders through an old cemetery and into a photo shoot, kidnaps the model (played by Eva Mendes), who doesn't appear to be lucid, and takes her to his lair where he eats some of her hair and then strips naked, revealing a full-on erection. That was the point when I realized I had wasted my "WTF" facial expression on Cosmopolis.

Holy Motors is the kind of film that people watch and say, "yes, those Europeans don't need logical plots. How sophisticated they are!" I think it's safe to say that not all Europeans will like Holy Motors. These kinds of films reveal a lot about Americans, particularly our ever-present fear of being considered less cultured than our forebears in Europe. I hope people who see Holy Motors for what it is will not be branded as unsophisticated narrative-junkies who curl up in the fetal position--screaming with moronic fury-- when the plot of a film isn't totally linear. At the same time, I realize it's foolish to want to lay down any hard-and-fast rules about what makes a good movie good (such as "a film's plot must be linear"). Those rules are always broken sooner or later, and the critics who nailed them onto the doors of the theater are soon yanking them off again--quietly, hoping nobody will hear them.

Edith Scob's performance as Oscar's driver, Celine, stands out as one of the few highlights of the film. She's not the type of person you imagine being a driver. (They're usually men, for some reason.) Her devotion to Oscar is unyielding, almost doting, but strictly professional, mostly. (She lets down her guard at the end, and it's kind of touching.) Kylie Minogue has an interesting scene near the end as Jean, a fellow actor who Oscar meets unexpectedly when their limos bump into each other. In one of the most bizarre scenes in the film (which must be some kind of an accomplishment), they wander through an abandoned department store, the ground of which is littered with dismembered mannequins, and Jean breaks into song, letting out vague but passionate clues about hers and Oscar's romantic past.

There are movies that are strange and unusual and complicated and wonderful. This just isn't one of them. The outre subject matter in Carax's film feels amiss, boring, meaningless, at times funny, confusing, yet obvious. It's a sort of faux mock-cleverness that's unaware of how insipid it is. For example: the model who allows herself to be kidnapped by Levant as the troll. She's blase during the entire scene, and the photographer allows her to be kidnapped. So we're never sure who is in on the act and who's not. But these motivations do not matter because the movie isn't that interesting. It's a spectacle with no meaning behind it. Perhaps some people will find it beautiful to look at.

With Elise L'Homeau and Jeanne Disson. Written by the director. 115 minutes.

November 16, 2012

Breaking Dawn Part 2

I didn't see Breaking Dawn Part 1, but it wasn't that hard to catch up with everyone's favorite shiny vampire couple, Bella and Edward, from where I left them at Eclipse. Breaking Dawn Part 2 is the payoff of the payoff. Finally all those who were too lazy to read the books can feel the exquisite relief of resolution. And to my surprise, Breaking Dawn Part 2 was a first-rate piece of entertainment, marked by brilliant writing (shout-out to screenwriter Melissa Rosenberg), heart-pounding suspense, breathtaking vistas of the Pacific Northwest, and a performance from Robert Pattinson that can only be summed up in one word: Brando.

Okay, none of this is true. But I've been criticized before for pointing out the shortcomings in this series. Nobody goes to see the Twilight movies for quality, they tell me. Okay, fine. But don't you have any standards? Actually, there were some improvements. This is the most entertaining entry I've seen. And the cast isn't as bad as it was before. For example, Kristen Stewart, whose acting has now been upgraded to corpse-plus rather than sub-corpse. She may eventually surpass Kevin Costner if she continues working long enough. (She actually seems to be feeling something this time around, definitely an encouraging sign.) Stewart's also gotten more beautiful--or at the very least, the pore refiner has increased in quality in proportion with the budget. She seems to be coming into her adulthood a little more, and that makes her more believable as a heroine. Maybe it's because she finally has some motivation beyond gushy teen love: a child of her own whom she must defend from the Volturi, that evil organization of vampires which rules all of nosferatudom and seems to be itching for a vampire vs. vampire battle. When they find out about Bella and Edward's daughter, they believe the Cullen family has broken an age-old law that forbids interbreeding between vampires and humans, and this escalates the conflict that was coming to a boil in the first four films.

Still, there's never any doubt as to how things will end up. You can hardly accuse this movie of being a cliffhanger. Okay, it's a simple matter of giving people what they want. And that's understandable. They've waited four years, for heaven's sake. What's more frustrating for a movie lover is to see a film so self-deluded: it thinks that the subdued kissing scenes and all the half-remorseful, half-horned-up glances are passion. This movie never achieves room temperature, let alone anything remotely hot enough to qualify as passion. Even the countless vampire decapitations--this film has more beheadings than Paris in 1794--lack integrity. (Obviously the filmmakers wanted a PG-13 rating, as their box office revenue depends upon the army of tweens who inundated the theater tonight.) When the vampires' heads are yanked out of their neck sockets, they look like china figures. One of them gets separated at the jaw line, but even this effect is too tame to elicit anything more than laughter. (Although the fans were cheering with reverie at each and every Volturi beheading.)

As for the other leads: Robert Pattinson is a fairly good actor, except he always seems to be playing boring roles. I think the camera itself fell in love with Pattinson. But it's not him really. It's the make-up: the pasty white skin that turns him into an emaciated-looking bloodsucker, and the burgundy lips that suggest a passionate fire underneath the cool exterior. He's the perfect Harlequin hero, and still homo-erotic enough when acting with his longtime frenemy Taylor Lautner that I would invest in their Bed & Breakfast in Vermont. (You can read about that in my Eclipse review.)

The problem with these movies has always been that everyone's too beautiful. That's the fantasy they're selling--that everyone's buying, it should be pointed out--but it really doesn't work for the genre, even if the Meyer vampire is a far cry from Bram Stoker's, or even the vampires of the 70s cult soap opera Dark Shadows. This is a Gothic for the Abercrombie & Fitch generation, which is to say it's a Gothic full of mannequins with empty heads.

The script, by Rosenberg (who has seen the series through to the end, valiantly unwilling to part with the banality of author Stephenie Meyer's ideas), hasn't a speck of irony about it, although there are a few funny parts. Most of them are little gifts, wafers for the initiated--those fans who've been faithful enough to sit through all five of the movies. There are moments where Edward and Jacob make little sarcastic comments too, showing a spark of self-awareness, and for those brief seconds the movie doesn't take itself too seriously.

But the director, Bill Condon, goes all-in in terms of giving you Twimaniacs your money's worth. Condon treats every scene either like he's uncorking a bottle of champagne or beholding the breathtaking wonder of Mount Everest. These rapturous renderings generally herald nothing more than inane twaddle between the vegetarian vampires, or "stirring" nature sequences, some of them looking a bit fakey. Bella and Edward hurdle through the crisp evergreens looking for animals to hunt, and she decides to go after a rock climber instead. A clever idea, except she's stopped by Edward and his commitment to being a decent vampire. (This film--and its predecessors-- would have been more intriguing with the ambiguity ratcheted up. Edward was never really bad enough to be the enticing rebel without a pulse. Maybe Bella could have led us delightfully astray by turning into a human-hunting bloodsucker. That would have given them an excuse for Breaking Dawn 3. But nobody's interested in seeing her veer from the straight-and-narrow. That, or the writers' idea of turning away from good is living forever young and sparkling in sunlight. How incredibly bad-ass.)

As the head villain, Michael Sheen turns in a performance that's like bad Dr. Evil. He sports a particularly lame make-up job, as one of my friends I saw the movie with pointed out to me. Sheen delivers a creepy laugh--a high-pitched, hollowed-out welt of a titter--that elicited a wave of guffaws from the audience. I was actually enjoying the audience more than the movie. Their applause was generous throughout, and you could certainly feel their excitement.

Some of the dialogue is delightfully bad. "Forever isn't as long as I'd hoped" comes to mind. Or, when Jacob refers to Bella's infant by the nickname Nessy, she exclaims with horrified indignation, "you nicknamed my daughter after the Loch Ness Monster?!" Kristen Stewart's voice is too flat to suggest real anger. All that moping she did in the first Twilight has paid off, though. It proves that pouty girls really can have it all.

With Peter Facinelli, Ashley Greene, Kellan Lutz, Billy Burke, Elizabeth Reaser, Dakota Fanning, Jamie Campbell Bower, Mackenzie Foy, Maggie Grace, and Jackson Rathbone. 108 mins.

Okay, none of this is true. But I've been criticized before for pointing out the shortcomings in this series. Nobody goes to see the Twilight movies for quality, they tell me. Okay, fine. But don't you have any standards? Actually, there were some improvements. This is the most entertaining entry I've seen. And the cast isn't as bad as it was before. For example, Kristen Stewart, whose acting has now been upgraded to corpse-plus rather than sub-corpse. She may eventually surpass Kevin Costner if she continues working long enough. (She actually seems to be feeling something this time around, definitely an encouraging sign.) Stewart's also gotten more beautiful--or at the very least, the pore refiner has increased in quality in proportion with the budget. She seems to be coming into her adulthood a little more, and that makes her more believable as a heroine. Maybe it's because she finally has some motivation beyond gushy teen love: a child of her own whom she must defend from the Volturi, that evil organization of vampires which rules all of nosferatudom and seems to be itching for a vampire vs. vampire battle. When they find out about Bella and Edward's daughter, they believe the Cullen family has broken an age-old law that forbids interbreeding between vampires and humans, and this escalates the conflict that was coming to a boil in the first four films.

Still, there's never any doubt as to how things will end up. You can hardly accuse this movie of being a cliffhanger. Okay, it's a simple matter of giving people what they want. And that's understandable. They've waited four years, for heaven's sake. What's more frustrating for a movie lover is to see a film so self-deluded: it thinks that the subdued kissing scenes and all the half-remorseful, half-horned-up glances are passion. This movie never achieves room temperature, let alone anything remotely hot enough to qualify as passion. Even the countless vampire decapitations--this film has more beheadings than Paris in 1794--lack integrity. (Obviously the filmmakers wanted a PG-13 rating, as their box office revenue depends upon the army of tweens who inundated the theater tonight.) When the vampires' heads are yanked out of their neck sockets, they look like china figures. One of them gets separated at the jaw line, but even this effect is too tame to elicit anything more than laughter. (Although the fans were cheering with reverie at each and every Volturi beheading.)

As for the other leads: Robert Pattinson is a fairly good actor, except he always seems to be playing boring roles. I think the camera itself fell in love with Pattinson. But it's not him really. It's the make-up: the pasty white skin that turns him into an emaciated-looking bloodsucker, and the burgundy lips that suggest a passionate fire underneath the cool exterior. He's the perfect Harlequin hero, and still homo-erotic enough when acting with his longtime frenemy Taylor Lautner that I would invest in their Bed & Breakfast in Vermont. (You can read about that in my Eclipse review.)

The problem with these movies has always been that everyone's too beautiful. That's the fantasy they're selling--that everyone's buying, it should be pointed out--but it really doesn't work for the genre, even if the Meyer vampire is a far cry from Bram Stoker's, or even the vampires of the 70s cult soap opera Dark Shadows. This is a Gothic for the Abercrombie & Fitch generation, which is to say it's a Gothic full of mannequins with empty heads.

The script, by Rosenberg (who has seen the series through to the end, valiantly unwilling to part with the banality of author Stephenie Meyer's ideas), hasn't a speck of irony about it, although there are a few funny parts. Most of them are little gifts, wafers for the initiated--those fans who've been faithful enough to sit through all five of the movies. There are moments where Edward and Jacob make little sarcastic comments too, showing a spark of self-awareness, and for those brief seconds the movie doesn't take itself too seriously.

But the director, Bill Condon, goes all-in in terms of giving you Twimaniacs your money's worth. Condon treats every scene either like he's uncorking a bottle of champagne or beholding the breathtaking wonder of Mount Everest. These rapturous renderings generally herald nothing more than inane twaddle between the vegetarian vampires, or "stirring" nature sequences, some of them looking a bit fakey. Bella and Edward hurdle through the crisp evergreens looking for animals to hunt, and she decides to go after a rock climber instead. A clever idea, except she's stopped by Edward and his commitment to being a decent vampire. (This film--and its predecessors-- would have been more intriguing with the ambiguity ratcheted up. Edward was never really bad enough to be the enticing rebel without a pulse. Maybe Bella could have led us delightfully astray by turning into a human-hunting bloodsucker. That would have given them an excuse for Breaking Dawn 3. But nobody's interested in seeing her veer from the straight-and-narrow. That, or the writers' idea of turning away from good is living forever young and sparkling in sunlight. How incredibly bad-ass.)

As the head villain, Michael Sheen turns in a performance that's like bad Dr. Evil. He sports a particularly lame make-up job, as one of my friends I saw the movie with pointed out to me. Sheen delivers a creepy laugh--a high-pitched, hollowed-out welt of a titter--that elicited a wave of guffaws from the audience. I was actually enjoying the audience more than the movie. Their applause was generous throughout, and you could certainly feel their excitement.

Some of the dialogue is delightfully bad. "Forever isn't as long as I'd hoped" comes to mind. Or, when Jacob refers to Bella's infant by the nickname Nessy, she exclaims with horrified indignation, "you nicknamed my daughter after the Loch Ness Monster?!" Kristen Stewart's voice is too flat to suggest real anger. All that moping she did in the first Twilight has paid off, though. It proves that pouty girls really can have it all.

With Peter Facinelli, Ashley Greene, Kellan Lutz, Billy Burke, Elizabeth Reaser, Dakota Fanning, Jamie Campbell Bower, Mackenzie Foy, Maggie Grace, and Jackson Rathbone. 108 mins.

November 12, 2012

The Perks of Being a Wallflower

In The Perks of Being a Wallflower, 15-year-old Charlie is recovering from a traumatic event in his life (the recent death of his best friend) and trying to adjust to high school. He soon finds a group of friends who haven't followed the herd mentality of adolescence, or so he thinks, and begins to find himself in them. Actually, when you read the plot of this movie in those terms, it sounds awfully cheap.

Some of the ideas in Wallflower seem so calculated to wrench out your heart that you feel writer-director Stephen Chbosky, who adapted the screenplay from his own 1999 novel, is performing the work of a surgeon, not a filmmaker. His movie resurrects a lot of the old devices and archetypes, including the hip, self-aware English teacher (Paul Rudd, more amiable than he's ever been because he doesn't appear to be trying so hard, nor does he seem as jaded as usual), and the parents who "just don't get it." Yes, Wallflower has most of the cliched ingredients of a teen drama. But yet it also has an effervescent sort of charm to it. You can't really feel any disdain for the world this film creates, because it's authentic, imaginative. Moreover, the relationships between adolescents and grown-ups and between adolescents and adolescents, is shown to be far more complex than "the parents just don't get it" or "the jocks don't talk to the geeks." It's refreshing.

Logan Lerman carries Wallflower with his wonderful performance, one of the strongest by an up-and-coming actor in recent memory. His Charlie feels the pain of everyone he knows, even of those who have caused him pain, and he can't let it go, or imagine it away. He reminded me of young Timothy Hutton in Ordinary People. Lerman makes it look so easy because he is, often, the most together of his friends (probably because he's hiding all his own problems so he won't fall apart.) The supporting cast includes Emma Watson, as Sam, the girl Charlie has a crush on, and Ezra Miller, as Patrick, Sam's step-brother, a remarkably self-aware young man who's also miserable because he's gay and has to keep his relationship with one of the football players a secret.

Wallflower is a wistful movie, one that makes you slightly depressed to have passed your teenage years, and slightly exuberant because you remember how bad they were, even if they weren't as cinematically bad as in this movie. (There are a lot of lovely moments in between the sad parts, though). I kept going back in my mind to John Hughes' movies, as they were, for me, the quintessential high school movies, even though they failed to reflect my own high school experience, which of course happened later than the 1980s. The high school experience that's reflected in Wallflower isn't in the same territory as a John Hughes movie though. It's more realistic, less sitcomish. You almost wish the John Hughes vision of high school life could be true, because it's such a fairy tale. Full of complications but all of them solved by the denouement. Wallflower won't solve the problems. It illuminates the people and leaves the problems where they are: some will go away with time, some won't. But the spirit that thrives in this joyful movie isn't nearly as temporal as those four years of prison, hell, and torment, or alternately freedom, euphoria, and excitement. And I liked that about it.

With Dylan McDermott and Kate Walsh as Charlie's parents, Johnny Simmons, Melanie Lynskey (as Charlie's Aunt Helen), Mae Whitman, Erin Wilhelmi, Joan Cusack, and Tom Savini. 102 min. ★★★½

Some of the ideas in Wallflower seem so calculated to wrench out your heart that you feel writer-director Stephen Chbosky, who adapted the screenplay from his own 1999 novel, is performing the work of a surgeon, not a filmmaker. His movie resurrects a lot of the old devices and archetypes, including the hip, self-aware English teacher (Paul Rudd, more amiable than he's ever been because he doesn't appear to be trying so hard, nor does he seem as jaded as usual), and the parents who "just don't get it." Yes, Wallflower has most of the cliched ingredients of a teen drama. But yet it also has an effervescent sort of charm to it. You can't really feel any disdain for the world this film creates, because it's authentic, imaginative. Moreover, the relationships between adolescents and grown-ups and between adolescents and adolescents, is shown to be far more complex than "the parents just don't get it" or "the jocks don't talk to the geeks." It's refreshing.

Logan Lerman carries Wallflower with his wonderful performance, one of the strongest by an up-and-coming actor in recent memory. His Charlie feels the pain of everyone he knows, even of those who have caused him pain, and he can't let it go, or imagine it away. He reminded me of young Timothy Hutton in Ordinary People. Lerman makes it look so easy because he is, often, the most together of his friends (probably because he's hiding all his own problems so he won't fall apart.) The supporting cast includes Emma Watson, as Sam, the girl Charlie has a crush on, and Ezra Miller, as Patrick, Sam's step-brother, a remarkably self-aware young man who's also miserable because he's gay and has to keep his relationship with one of the football players a secret.

Wallflower is a wistful movie, one that makes you slightly depressed to have passed your teenage years, and slightly exuberant because you remember how bad they were, even if they weren't as cinematically bad as in this movie. (There are a lot of lovely moments in between the sad parts, though). I kept going back in my mind to John Hughes' movies, as they were, for me, the quintessential high school movies, even though they failed to reflect my own high school experience, which of course happened later than the 1980s. The high school experience that's reflected in Wallflower isn't in the same territory as a John Hughes movie though. It's more realistic, less sitcomish. You almost wish the John Hughes vision of high school life could be true, because it's such a fairy tale. Full of complications but all of them solved by the denouement. Wallflower won't solve the problems. It illuminates the people and leaves the problems where they are: some will go away with time, some won't. But the spirit that thrives in this joyful movie isn't nearly as temporal as those four years of prison, hell, and torment, or alternately freedom, euphoria, and excitement. And I liked that about it.

With Dylan McDermott and Kate Walsh as Charlie's parents, Johnny Simmons, Melanie Lynskey (as Charlie's Aunt Helen), Mae Whitman, Erin Wilhelmi, Joan Cusack, and Tom Savini. 102 min. ★★★½

November 10, 2012

For Your Consideration

Of all Christopher Guest's comedies, For Your Consideration (2006) emerges as the most uncanny in its portrayals, this time of Hollywood. (Perhaps this is because I'm more familiar with movies than I am with folk musicians, dog trainers, and local theater.) Guest co-wrote the script with Eugene Levy, both of whom appear, along with the usual suspects, playing various members of the Hollywood community, from actors to crew members to publicists and talk show hosts.

If there is a central character, it's Marilyn Hack (played with stunning, hallucinatory, grotesque perfection by the great Catherine O'Hara). Marilyn is a virtual has-been actress who is finally returning to the silver screen in an over-the-top soaper that's part Tennessee Williams, part From Here to Eternity. It's a turbulent drama about a Jewish family's frosty reunion during the Purim holiday season, aptly titled Home For Purim. Marilyn hears rumors, via the internet, about an Oscar nomination coming her way, and inflates the rumors into Oscar buzz, some fake fairy dust that soon sprinkles onto the heads of her co-stars, played by Harry Shearer, Parker Posey, and Christopher Moynihan.

It's tragically funny to watch all the bees working their industry, all of them vying for queenhood, some of them with expert precision, others with an astonishing lack of self-awareness. You can only emerge from this movie feeling you've looked directly into the tortured, ironic, narcissistic soul of Hollywood itself, as though this least-documentary of all Guest's films is the one actual documentary: a record as exact and untouched by narrative intention as C-SPAN.

The supporting cast includes scene-stealing Fred Willard as the co-host of a movie talk show. He's really on fire in this movie, whipping out little throwaway lines with stunning ease and subtlety: his character seems like a complete moron, yet he's also brimming with ironic hostility, aimed at the Hollywood types that make his show. Jane Lynch plays his co-star. She's a delight, but she is a overshadowed by Willard's hammy deviousness. Jennifer Coolidge plays a dippy producer who appears to be constantly drunk. Coolidge never gets as much screen time as you'd want, considering how funny she is. With John Michael Higgins, Ed Begley, Jr., Bob Balaban, Michael McKean, and Carrie Aizley; and in cameo appearances: Ricky Gervais, Sandra Oh, John Krasinski, Paul Dooley, Hart Bochner, and Claire Forlani.

If there is a central character, it's Marilyn Hack (played with stunning, hallucinatory, grotesque perfection by the great Catherine O'Hara). Marilyn is a virtual has-been actress who is finally returning to the silver screen in an over-the-top soaper that's part Tennessee Williams, part From Here to Eternity. It's a turbulent drama about a Jewish family's frosty reunion during the Purim holiday season, aptly titled Home For Purim. Marilyn hears rumors, via the internet, about an Oscar nomination coming her way, and inflates the rumors into Oscar buzz, some fake fairy dust that soon sprinkles onto the heads of her co-stars, played by Harry Shearer, Parker Posey, and Christopher Moynihan.

It's tragically funny to watch all the bees working their industry, all of them vying for queenhood, some of them with expert precision, others with an astonishing lack of self-awareness. You can only emerge from this movie feeling you've looked directly into the tortured, ironic, narcissistic soul of Hollywood itself, as though this least-documentary of all Guest's films is the one actual documentary: a record as exact and untouched by narrative intention as C-SPAN.

The supporting cast includes scene-stealing Fred Willard as the co-host of a movie talk show. He's really on fire in this movie, whipping out little throwaway lines with stunning ease and subtlety: his character seems like a complete moron, yet he's also brimming with ironic hostility, aimed at the Hollywood types that make his show. Jane Lynch plays his co-star. She's a delight, but she is a overshadowed by Willard's hammy deviousness. Jennifer Coolidge plays a dippy producer who appears to be constantly drunk. Coolidge never gets as much screen time as you'd want, considering how funny she is. With John Michael Higgins, Ed Begley, Jr., Bob Balaban, Michael McKean, and Carrie Aizley; and in cameo appearances: Ricky Gervais, Sandra Oh, John Krasinski, Paul Dooley, Hart Bochner, and Claire Forlani.

November 08, 2012

Singin' in the Rain

Singin' in the Rain (1952) is perhaps the best movie musical ever made. It's a clever satire of the movie industry during its exciting but traumatic and precarious transition from the silent era to talking pictures. The satire is always well-crafted but never mean-spirited, and it would have been the perfect movie musical, except for two laboriously overlong dance numbers in the second half of the film. (Both of which seem like obvious padding and represent the only real lapses in judgment of the directors, Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly.)

Unlike most musicals, the songs don't seem incidental to the plot, and they're worked into the story sporadically and contextually (most of the time), rather than every five minutes whether it works for the movie or not. Gene Kelly, Donald O'Connor, and Debbie Reynolds head the cast. Kelly plays Don Lockwood, a silent screen star who sees star quality in the plucky girl-next-door Kathy Selden (Reynolds), whom he meets while running away from "adoring" fans trying to tear off pieces of his suit as souvenirs.

As Cosmo Brown, Don Lockwood's best friend and former Vaudeville partner (and a talented singer, dancer and musician in his own right), Donald O'Connor shines, like an early version of Sean Hayes, but with far more mock innocence. He's this movie's comic relief, always ready with a comical expression or a good quip to deflate the pomposity of the studio execs or disarm the stupidity of the movie stars. He would have saved just about any movie from total destruction, except Singin' in the Rain has the graciousness not to be self-important, so it doesn't need saving. There's no dewy-eyed sincerity here: instead, it's a glamorous, exquisite jab at the falseness of Hollywood personalities and the tomfoolery of showbusiness.

Jean Hagen plays Lina Lamont, a popular actress because of her beauty, who possesses a shrill, unsophisticated speaking voice that's sure to ruin not only her career but also her studio (called Monumental Pictures), once it begins producing "talkies". Enter Debbie Reynolds, whose beautiful singing and speaking voice is dubbed over Lina's crowing, to give the endangered star some legitimacy in the new wave of sound.

The best songs in the film are O'Connor's rendition of "Make 'Em Laugh," "Good Morning" and the titular number, done with style and joyous aplomb by Gene Kelly, who is ever the performer's performer. Nacio Herb Brown and Arthur Freed contributed most of the songs. The choreography is mostly smart, although one does grow weary of watching Gene Kelley tap dance after a while.

Rita Moreno appears in a bit part. With Millard Mitchell, Cyd Charisse, Douglas Fowley, King Donovan, and Madge Blake.

Unlike most musicals, the songs don't seem incidental to the plot, and they're worked into the story sporadically and contextually (most of the time), rather than every five minutes whether it works for the movie or not. Gene Kelly, Donald O'Connor, and Debbie Reynolds head the cast. Kelly plays Don Lockwood, a silent screen star who sees star quality in the plucky girl-next-door Kathy Selden (Reynolds), whom he meets while running away from "adoring" fans trying to tear off pieces of his suit as souvenirs.

As Cosmo Brown, Don Lockwood's best friend and former Vaudeville partner (and a talented singer, dancer and musician in his own right), Donald O'Connor shines, like an early version of Sean Hayes, but with far more mock innocence. He's this movie's comic relief, always ready with a comical expression or a good quip to deflate the pomposity of the studio execs or disarm the stupidity of the movie stars. He would have saved just about any movie from total destruction, except Singin' in the Rain has the graciousness not to be self-important, so it doesn't need saving. There's no dewy-eyed sincerity here: instead, it's a glamorous, exquisite jab at the falseness of Hollywood personalities and the tomfoolery of showbusiness.

Jean Hagen plays Lina Lamont, a popular actress because of her beauty, who possesses a shrill, unsophisticated speaking voice that's sure to ruin not only her career but also her studio (called Monumental Pictures), once it begins producing "talkies". Enter Debbie Reynolds, whose beautiful singing and speaking voice is dubbed over Lina's crowing, to give the endangered star some legitimacy in the new wave of sound.

The best songs in the film are O'Connor's rendition of "Make 'Em Laugh," "Good Morning" and the titular number, done with style and joyous aplomb by Gene Kelly, who is ever the performer's performer. Nacio Herb Brown and Arthur Freed contributed most of the songs. The choreography is mostly smart, although one does grow weary of watching Gene Kelley tap dance after a while.

Rita Moreno appears in a bit part. With Millard Mitchell, Cyd Charisse, Douglas Fowley, King Donovan, and Madge Blake.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

_poster.jpg)