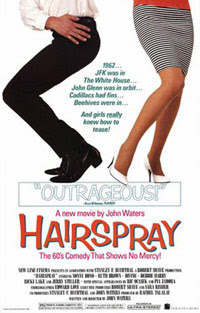

It was inevitable that filmmaker John Waters, Baltimore's King of Trash, would go mainstream, if only briefly. His Hairspray (1988) is an affectionately kitschy tale of dancing and integration in 1962 Baltimore. Ricki Lake plays the heroine, Tracy Turnblad, who is probably the first fat girl to be the star of any teen comedy. It's a wonderful thing: finally a movie that doesn't glorify skinny little things. It vilifies them instead. Waters revels in the bad taste of middle-class Americans, and even when he's doing it for a mass audience, he manages to be coy and ironic (without seeming mean-spirited, no mean feat.) The mainstreaming of Waters' schtick works for him: it evens out some of the over-indulgent aspects of his brand of filmmaking. Hairspray feels like a movie, where some of his earlier films (such as the notorious 1972 cult film Pink Flamingos) had that insufferable "home movie" feel to them which made watching tedious, even as you waited eagerly for the next shocking moment.

Lake's mother is played by the inimitable Divine, the drag queen who worked on almost every John Waters picture. Divine died unexpectedly, just a week after Hairspray opened. Divine has always imbued Waters' pictures with a sense of legitimate American white trashiness. As Tracy's mom, Divine is quite a showpiece, draped in a moo-moo, sporting a long black wig, and that wonderfully campy, butch persona. Divine's bizarreness keeps Hairspray from ever looking like some benign Hollywoodized teen comedy.

And the supporting cast is equally marvelous and macabre: Sonny Bono (the ultimate used car salesman of cinema) and Debbie Harry (sporting an outlandish blonde wig that transcends the campy fashion that Harry has always brandished as the frontwoman for the punk rock band Blondie) as the villains, Franklin and Velma Von Tussle; Colleen Fitzpatrick as their daughter, Amber (she looks like Kelly Preston), who hates Tracy because she becomes a popular regular on a local TV program called "The Corny Collins Show," whose host (played by Shawn Thompson) is sort of Baltimore's Ed Sullivan (a young Ed Sullivan). Ruth Brown turns in a deliciously fun performance as "Motormouth Maybelle," the black diva who is friends with the "Corny Collins Show" and helps unite the black and white communities with her goofy rhyme-speech. She's a hoot; The always hilarious Jerry Stiller plays Tracy's dad. He has a wonderful kookiness about him that makes him look simultaneously out of it and sharp as a tack; Michael St. Gerard plays Link, the boy who falls in love with Tracy on the dance floor (he looks astonishingly like Elvis Presley, and even played him in the movie Great Balls of Fire!); Leslie Ann Powers plays Tracy's best friend Penny; Clayton Prince as Seaweed; Waters regular Mink Stole plays Corny's assistant, Tammy; and Joanna Havrilla plays Penny's uptight mom, Prudence, who's so terrified of black people that she hands a black man her wallet while walking through the Baltimore ghetto, assuming he's trying to rob her when he isn't.

July 31, 2012

July 29, 2012

Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

Richard Burton as George, a prickly, passive-aggressive history professor and Elizabeth Taylor as Martha, his bitter wife, who's the daughter of the president of the college where her husband teaches. They have a young couple (George Segal and Sandy Dennis) over for drinks, late one night after a faculty gathering at the college. Their little after-party turns out to be an opportunity for spectacle that playwright Edward Albee and sceenwriter Ernest Lehman couldn't resist. A night with George and Martha is pure masochism. Burton and Taylor fight like two cats as they churn out clever insults and fling them at each other with ruthless precision. As "raw" as this movie purports to be, it all feels too much like "acting." But the actors are still very good, even if the screenwriting is obviously trying to be "real" and "edgy." It's overly self-conscious, but first-time director Mike Nichols doesn't seem to worried about concealing it, which may be one of the reasons this canned drama works, as an exercise in frothy unpleasantness, but it's hard to watch this and call it a good time. These are some of the most unpleasant people you could ever spend an evening with, and while there's some humor in it, it feels too much like watching movie stars behind-the-scenes after they've had too much to drink.

There is a bit of style to it (Haskell Wexler won an Oscar for his black-and-white cinematography, and the editing by Sam O'Steen nicely lifts the material off the stage, even though it's still very much a talky film), and in 1966, this was probably a lot more exciting than it is in the era of celebrity meltdowns and the desensitizing spectacle that is reality television. I keep wondering: Were people really enjoying, even reveling in, Elizabeth Taylor as the frumpy drunk with the acid tongue? You really miss the Elizabeth Taylor of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Giant and even Suddenly, Last Summer, the one you could root for, even when she was over-acting. She always looked so ravishing, and exuded such electricity on the screen. She turned each of those roles into a performance. That's what's so enthralling, to this day, about Elizabeth Taylor, the movie star. She certainly gives us a performance in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, but somehow, seeing her turn into a vulgar lush (still pretty sexy though) is a disappointment. She won her second Oscar for this movie, and it's as if she had to go ugly and mean to get it. (She won her first Oscar for playing a high-class hooker who's killed in a car crash at the end of Butterfield 8, and the Academy was most rewarding as a result of her punishment.) But when an actress like Elizabeth Taylor is awarded for giving the kind of antithetical performance (and yes, it's a damn good one at times) she gives in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, it's a reminder of something that Taylor in her prime always helped us forget: that stars weren't real.

When they're drunk, though, Burton and Taylor have a wonderfully funny chemistry together. And George Segal is enjoyably perplexed as the young new biology professor who, along with his wife, becomes a pawn in George and Martha's matrimonial boxing match. (Sandy Dennis has a bubbly, aloof charm to her, and she gets to have her own mad meltdown as the night winds on and more skeletons tumble recklessly out everybody's closet. This feels like Albee's version of a Tennessee Williams play, full of corny, histrionic lines that are delivered with the right amount of tongue-in-cheek from this cast. They give each bad line a bit of ersatz class. (It would be frightening to see this performed by amateurs.)

There is a bit of style to it (Haskell Wexler won an Oscar for his black-and-white cinematography, and the editing by Sam O'Steen nicely lifts the material off the stage, even though it's still very much a talky film), and in 1966, this was probably a lot more exciting than it is in the era of celebrity meltdowns and the desensitizing spectacle that is reality television. I keep wondering: Were people really enjoying, even reveling in, Elizabeth Taylor as the frumpy drunk with the acid tongue? You really miss the Elizabeth Taylor of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Giant and even Suddenly, Last Summer, the one you could root for, even when she was over-acting. She always looked so ravishing, and exuded such electricity on the screen. She turned each of those roles into a performance. That's what's so enthralling, to this day, about Elizabeth Taylor, the movie star. She certainly gives us a performance in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, but somehow, seeing her turn into a vulgar lush (still pretty sexy though) is a disappointment. She won her second Oscar for this movie, and it's as if she had to go ugly and mean to get it. (She won her first Oscar for playing a high-class hooker who's killed in a car crash at the end of Butterfield 8, and the Academy was most rewarding as a result of her punishment.) But when an actress like Elizabeth Taylor is awarded for giving the kind of antithetical performance (and yes, it's a damn good one at times) she gives in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, it's a reminder of something that Taylor in her prime always helped us forget: that stars weren't real.

When they're drunk, though, Burton and Taylor have a wonderfully funny chemistry together. And George Segal is enjoyably perplexed as the young new biology professor who, along with his wife, becomes a pawn in George and Martha's matrimonial boxing match. (Sandy Dennis has a bubbly, aloof charm to her, and she gets to have her own mad meltdown as the night winds on and more skeletons tumble recklessly out everybody's closet. This feels like Albee's version of a Tennessee Williams play, full of corny, histrionic lines that are delivered with the right amount of tongue-in-cheek from this cast. They give each bad line a bit of ersatz class. (It would be frightening to see this performed by amateurs.)

Dead Man

A dull Western about a man named William Blake (Johnny Depp) who takes it on the lam after he kills a another man, sort of in self-defense. Then he meets an Indian named Nobody who spouts off philosophical sounding ramblings that make no sense. Writer-director Jim Jarmusch confuses pretension for art with this antithetical Western. It's in black-and-white, a crucial mistake. Perhaps some color would have made the movie feel less embalmed, but I'm afraid that was Jarmusch's intent all along: he's trying to make something poetic, and all he really does is make a film that reminds us why we hate bad poetry, or why we don't give poetry a chance when it's delivered to us without imagination.

The camera stays in close-up for much of the film, so we don't even get the usually standard pleasure of the vastness of space that many Westerns capture. This, combined with the grim ugliness of the black-and-white photography, makes much of Dead Man pretty dead indeed. Johnny Depp is okay, especially since he's playing a relatively normal character, but he's such a subdued personality when he's not hamming it up, that he's hardly magnetic enough to pull this long, meandering movie out of its self-induced sleepwalk. If people were mesmerized by all the poetry of the black-and-white and the false wisdom of the mystical "Nobody," it's because they were probably ready to embrace something that was different, and there weren't many good traditional Westerns coming out of the 1990s. But turning this genre into something bland and plodding is no way to save it from the tiredness of doing the same thing over and over.

There are interesting moments, and at times Jarmusch finds the humor in it. Some of the bandits trying to capture William Blake--who's got a 500 dollar bounty placed on him by the father of the man he killed--are funny in a ruthlessly sick sort of way, like the man who allegedly murdered his parents, and then engaged in necrophilia and cannibalism with their bodies. And the character of Nobody doesn't seem to totally buy into the BS he's peddling to William. Is he an ironic Indian? (He's also convinced that William is the William Blake, as in the 18th century British Romanticist poet.) But, like Dances With Wolves, the film tries to imbibe the Native Americans with wisdom and mystical powers, all dispensed in the form of hokey sounding proverbs, and you never buy any of it: it's too patronizing, and too laughable. It's the never-ending search for self-importance that dooms so many "indie" films. (There's also a running joke about tobacco that isn't funny--it's done to death and never had any juice to begin with.)

With Gary Farmer as Nobody, John Hurt, Lance Henriksen, Michael Wincott, Eugene Byrd, Iggy Pop, Gabriel Byrne, Jared Harris, Mili Avital, Crispin Glover, Robert Mitchum in a small role as the man who's funding Blake's capture. Neil Young provides the one-note music score via his electric guitar. It's simply anachronistic, and one more part of Dead Man that enervates the entire movie. 1995.

The camera stays in close-up for much of the film, so we don't even get the usually standard pleasure of the vastness of space that many Westerns capture. This, combined with the grim ugliness of the black-and-white photography, makes much of Dead Man pretty dead indeed. Johnny Depp is okay, especially since he's playing a relatively normal character, but he's such a subdued personality when he's not hamming it up, that he's hardly magnetic enough to pull this long, meandering movie out of its self-induced sleepwalk. If people were mesmerized by all the poetry of the black-and-white and the false wisdom of the mystical "Nobody," it's because they were probably ready to embrace something that was different, and there weren't many good traditional Westerns coming out of the 1990s. But turning this genre into something bland and plodding is no way to save it from the tiredness of doing the same thing over and over.

There are interesting moments, and at times Jarmusch finds the humor in it. Some of the bandits trying to capture William Blake--who's got a 500 dollar bounty placed on him by the father of the man he killed--are funny in a ruthlessly sick sort of way, like the man who allegedly murdered his parents, and then engaged in necrophilia and cannibalism with their bodies. And the character of Nobody doesn't seem to totally buy into the BS he's peddling to William. Is he an ironic Indian? (He's also convinced that William is the William Blake, as in the 18th century British Romanticist poet.) But, like Dances With Wolves, the film tries to imbibe the Native Americans with wisdom and mystical powers, all dispensed in the form of hokey sounding proverbs, and you never buy any of it: it's too patronizing, and too laughable. It's the never-ending search for self-importance that dooms so many "indie" films. (There's also a running joke about tobacco that isn't funny--it's done to death and never had any juice to begin with.)

With Gary Farmer as Nobody, John Hurt, Lance Henriksen, Michael Wincott, Eugene Byrd, Iggy Pop, Gabriel Byrne, Jared Harris, Mili Avital, Crispin Glover, Robert Mitchum in a small role as the man who's funding Blake's capture. Neil Young provides the one-note music score via his electric guitar. It's simply anachronistic, and one more part of Dead Man that enervates the entire movie. 1995.

July 28, 2012

Z

A fascinating look at the 1963 assassination of Greek pacifist and political activist Grigoris Lambrakis, Z (1969) is a fast-moving study of political corruption and the subtle ways government uses red tape and compartmentalization to aid its own propaganda and silence voices of dissent. Director Costa-Gavras is Greek by nationality, but his film is in French, where he has lived since the 1950s. It's an astonishing comment on corruption both right and left, and it's surprisingly energetic for such a talky film. You don't generally expect these kinds of movies to hold up 40-something years later, but the camera remains a fluid eyewitness to what feels at many times like a documentary. It's as if you're watching a rapidly edited version of C-Span, with intermingled shots of people protesting in streets, and of revolutionaries being attacked by the police and their paid hoods. For people who imagine the future as one of Orwellian proportions, Z suggests that we're in for more of this subtler kind of sleazy erasure of facts, doctoring of evidence, and manipulation (or silencing) of anyone who's willing to speak the truth. It's not as overtly horrific as something like 1984. It's the game of being powerful enough to pay off your enemies, or have them killed in "accidental" car accidents, or their autopsies re-written to corroborate falsified accounts.

Z was the first foreign film to be nominated for a Best Picture Academy Award (it won in the Best Foreign Language category). But it deserves more recognition for its witty and insightful view into post-WW2 international politics. It may have been all the more timely in terms of its reception in the U.S. because of our own notorious assassinations and their associated plots, however real or imagined. The world of Z is frighteningly real and present (even as this film nears 50 years in age), and it has an ominously prophetic view of the media's involvement in political maneuvering.

With Jean-Louis Tringtignant, Yves Montand, Irene Papas, Jacques Perrin, Charles Denner, Francois Perier, Pierre Dux, George Geret, Bernard Fresson, Marcel Bozzuffi, Julien Guiomar, Magali Noel, and Renato Salvatori. Written by Costa-Gavras and Jorge Semprun. Edited by Francoise Bonnot. Cinematography by Raoul Coutard.

Z was the first foreign film to be nominated for a Best Picture Academy Award (it won in the Best Foreign Language category). But it deserves more recognition for its witty and insightful view into post-WW2 international politics. It may have been all the more timely in terms of its reception in the U.S. because of our own notorious assassinations and their associated plots, however real or imagined. The world of Z is frighteningly real and present (even as this film nears 50 years in age), and it has an ominously prophetic view of the media's involvement in political maneuvering.

With Jean-Louis Tringtignant, Yves Montand, Irene Papas, Jacques Perrin, Charles Denner, Francois Perier, Pierre Dux, George Geret, Bernard Fresson, Marcel Bozzuffi, Julien Guiomar, Magali Noel, and Renato Salvatori. Written by Costa-Gavras and Jorge Semprun. Edited by Francoise Bonnot. Cinematography by Raoul Coutard.

The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert

Three drag queens in Australia go on a road trip to do some shows. It's sort of a combination of Easy Rider, a John Waters movie minus most of the vulgarity, and a Village People concert. The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert features standout performances by the three leads: Terence Stamp, as the aging drag queen who's getting tired of being in the biz, Hugo Weaving, whose character has the closest link to a "normal life" (he's got a wife and a kid, but he doesn't see much of them), and Guy Pearce, as the most rambunctious of the trio. It's quite an entertainment, particularly when the guys put on their outlandish outfits and lip sync to Donna Summer, ABBA, Vanessa Williams, and a number of other pop music numbers. (The costumes even won an Academy Award.)

For straight men playing gay men in drag, these three are remarkably uninhibited, especially Pearce, who struts around like a peacock with a wig collection as varied as its feathers. And Stamp manages to bring subtlety and graciousness to a role that could very easily have turned into pure camp. He's grieving over the loss of his partner, and agrees to accompany the other boys for a change of scenery, never suspecting it may lead to new opportunities romantically speaking, when he meets an incredulously open-minded rural mechanic, who's married to a kooky mail-order-bride who herself likes to put on a show at the local bar (after she's had too much to drink). Weaving's storyline, in which he's headed for a rekindling of his relationship with his young son, feels almost too carefully designed to tug at the heart strings, particularly when the boy is revealed to be far more open-minded than his father imagined he would be. At the same time, you have to hand it to writer-director Stephan Elliott, who knows when to be garishly offbeat and when to be subtle and unashamedly sweet. It's a welcome dose of eccentricity mixed with heart that most movies seem to have forgotten.

With Bill Hunter, Sarah Chadwick, and Mark Holmes. 1994.

For straight men playing gay men in drag, these three are remarkably uninhibited, especially Pearce, who struts around like a peacock with a wig collection as varied as its feathers. And Stamp manages to bring subtlety and graciousness to a role that could very easily have turned into pure camp. He's grieving over the loss of his partner, and agrees to accompany the other boys for a change of scenery, never suspecting it may lead to new opportunities romantically speaking, when he meets an incredulously open-minded rural mechanic, who's married to a kooky mail-order-bride who herself likes to put on a show at the local bar (after she's had too much to drink). Weaving's storyline, in which he's headed for a rekindling of his relationship with his young son, feels almost too carefully designed to tug at the heart strings, particularly when the boy is revealed to be far more open-minded than his father imagined he would be. At the same time, you have to hand it to writer-director Stephan Elliott, who knows when to be garishly offbeat and when to be subtle and unashamedly sweet. It's a welcome dose of eccentricity mixed with heart that most movies seem to have forgotten.

With Bill Hunter, Sarah Chadwick, and Mark Holmes. 1994.

July 23, 2012

Weird Science

Risky Business meets Frankenstein. Two unpopular high school boys (Anthony Michael Hall and Ilan-Mitchell Smith) use a computer to design the perfect girl. To their surprise, it actually works. Kelly LeBrock's performance, as the man-made beauty who helps her makers become less uptight, is this movie's most obvious charm. She's a lot of fun, and when the movie takes a turn for the chaotic (during a big party scene, where a gang of mutants trashes the house), her casual, go-with-the-flow mood is a welcome respite. This isn't the smartest comedy writer-director John Hughes ever came up with. It's too much of a male wish fulfillment fantasy. But it's got some fun moments, and a few up-and-coming actors turn up here in supporting roles: Robert Downey Jr., Bill Paxton, Robert Rusler, and Suzanne Snyder. Followed by a short-lived television series. 1985

July 22, 2012

Vamp

Low-grade horror-comedy about two buddies who stumble upon a strip club full of vampires in a city that is, by night, a hot-bed of bloodsuckers. The "head" vampire, Katrina (Grace Jones), is a tall, fangy creature with Egyptian roots, so the movie suggests. But she's really not that scary or intimidating, and unlike the suave, charming vampire Chris Sarandon played in the original Fright Night, she isn't any fun. She's just a freak.

Chris Makepeace and Robert Rusler have an amiable chemistry together, especially in the beginning when they're being hazed by a particularly infantile group of frat brothers. But the film doesn't make much use out of that charm. Director Richard Wenk (he co-wrote the screenplay with Donald Borchers) doesn't have much of a flair for creating suspenseful situations. The movie has a nice comic book feel, but the simple-minded plot keeps it from generating into anything fun or exciting. Just about every scene promises more than it delivers: Makepeace is chased by a gang of thugs into a sewer system, which seems like it could have been used for a good scare sequence, but the thugs don't go in after him, and it lessens the impact.

There's an odd combination of green and pink neon lighting that permeates the movie, giving it a nice "red light district" feeling, but it's overused, and it doesn't do much more than conceal the fact that the movie wasn't designed with much thought or imagination. The lighting becomes a crutch rather than an enhancer of real atmosphere. With Dedee Pfeiffer, Gedde Watanabe, and, in an amusing role as Katrina's guardian/manager, Sandy Baron. 1986.

Chris Makepeace and Robert Rusler have an amiable chemistry together, especially in the beginning when they're being hazed by a particularly infantile group of frat brothers. But the film doesn't make much use out of that charm. Director Richard Wenk (he co-wrote the screenplay with Donald Borchers) doesn't have much of a flair for creating suspenseful situations. The movie has a nice comic book feel, but the simple-minded plot keeps it from generating into anything fun or exciting. Just about every scene promises more than it delivers: Makepeace is chased by a gang of thugs into a sewer system, which seems like it could have been used for a good scare sequence, but the thugs don't go in after him, and it lessens the impact.

There's an odd combination of green and pink neon lighting that permeates the movie, giving it a nice "red light district" feeling, but it's overused, and it doesn't do much more than conceal the fact that the movie wasn't designed with much thought or imagination. The lighting becomes a crutch rather than an enhancer of real atmosphere. With Dedee Pfeiffer, Gedde Watanabe, and, in an amusing role as Katrina's guardian/manager, Sandy Baron. 1986.

Union City

Hardly the debut you would want for rock 'n' roll's sexiest icon, Deborah Harry. It's a dreadfully dull, plodding, cheap-looking film noir drama from a short story by Cornell Woolrich. Harry plays a frumpy housewife whose husband (Dennis Lipscomb) accidentally murders a homeless man, and then conceals him in their Union City, New Jersey apartment. It's 90 minutes of pure nothingness, and it isn't even the kind of bad movie you can laugh at. It's just painful. Harry proved she could be a lot of fun on the screen in movies like John Waters' Hairspray (1988), but in this, she plays down everything that's hip and self-parodying about her. Even the blonde hair is eschewed in favor of her natural brunette color. When her character decides to go blonde at the end, it's a remarkable transformation that comes too late to be of any help to this mess. (The smartest thing Debbie Harry ever did for her career was buy a bottle of Peroxide and embrace a campy, mock-dull attitude.) A movie that tries to go against the best attributes of its cast is almost certainly doomed for failure. The bad filmmaking doesn't help either. It's poorly lit and visually unimaginative. With Everett McGill, Sam McMurray, Irina Maleeva, and, in a small role, Pat Benatar. Directed by Marcus Reichert. The undistinguished music score is by Chris Stein, Harry's Blondie co-founder and one-time boyfriend. 1980.

July 20, 2012

Jaws

In Jaws (1975), a Northeastern beachfront town called Amity Island is threatened by a massive, aggressive Great White Shark. Despite three horrendous attacks on swimmers, the mayor and the small business owners put up a fight when the police chief (Roy Scheider) decides to close down the beaches. It's good old capitalism at work. Some critics have lamented that Jaws is some kind of left-wing attack on the free market, but are they in favor of sending droves of swimmers into the beaches to be eaten alive? The police chief has his hands full between the pressure from the public to catch the shark and the pressure from the local government to keep the beaches open (and thus, to keep the town's economy thriving.) He enlists the help of an egghead oceanographer (Richard Dreyfuss) and a crusty old sailor (Robert Shaw) to catch the mammoth shark.

Jaws is a casebook example of the old monster-movie rule: show as little of the monster as possible for as long as possible. That way, the audience members have built up a picture of the beast in their minds that's far more terrifying than the actual thing, the eventual revelation of which then amplifies the terror. Apparently, director Steven Spielberg and his crew began referring to their movie as "Flaws" during the shoot, because they believed it wasn't going to work. The public thought differently, and Jaws was an enormous hit. The film's financial success--unexpected as it was--had far-reaching consequences, creating the "summer blockbuster movie." Between Jaws and Star Wars, a lot of damage was done to filmmakers who wanted to get funding for smaller movies. If studios could get a crowd-pleasing product like Jaws out, and make a bundle on it (not to mention all the money made via the connected merchandise), then taking risks on so-called "little" movies became even more dangerous and unappealing. Jaws is an efficient, expert thriller, bolstered by a leavening sense of humor and three strong leads, but it's hard not to feel somewhat frustrated by the consequences of its success.

The fun thing about Jaws is in watching how the filmmakers tried to get around actually showing us their beast. The editor, Verna Fields (who won an Oscar for her work), keeps the scare sequences moving, never letting us rest too long on one given image. But she also spends enough time with each shot to let us take in what's happening. That balance gives Jaws a certain charm when compared to today's thrillers, which cut so fast we're often completely in the dark about what's going on. Nothing turns the audience off like being kept out of the loop, and yet it seems to have become a popular movie-making trend, perhaps a cheap way to conceal mistakes from observant movie-goers. With Jaws, we're completely invested, and that ramps up the suspense even more.

I think the biggest problem I have with Jaws is how much it's been built up over the years as a classic. It's better when you don't have such grandiose expectations for it. Then you can sit back and let it entertain you. There are slow spots: the last thirty minutes get to be quite repetitive and you wish they'd just hurry up and kill the damn thing. But the big crowd scenes are well-thought-out for the most part, and there's enough energy and excitement in them to sustain you through the periodic lulls in the movie. And Scheider has great chemistry with Dreyfuss, and with Lorraine Gary, who plays his wife.

With Murray Hamilton as the mayor of Amity Island and Jeffrey Kramer as Scheider's deputy. Adapted by Carl Gottlieb and Peter Benchley from Benchley's novel. John Williams composed the now famous music score.

Jaws is a casebook example of the old monster-movie rule: show as little of the monster as possible for as long as possible. That way, the audience members have built up a picture of the beast in their minds that's far more terrifying than the actual thing, the eventual revelation of which then amplifies the terror. Apparently, director Steven Spielberg and his crew began referring to their movie as "Flaws" during the shoot, because they believed it wasn't going to work. The public thought differently, and Jaws was an enormous hit. The film's financial success--unexpected as it was--had far-reaching consequences, creating the "summer blockbuster movie." Between Jaws and Star Wars, a lot of damage was done to filmmakers who wanted to get funding for smaller movies. If studios could get a crowd-pleasing product like Jaws out, and make a bundle on it (not to mention all the money made via the connected merchandise), then taking risks on so-called "little" movies became even more dangerous and unappealing. Jaws is an efficient, expert thriller, bolstered by a leavening sense of humor and three strong leads, but it's hard not to feel somewhat frustrated by the consequences of its success.

The fun thing about Jaws is in watching how the filmmakers tried to get around actually showing us their beast. The editor, Verna Fields (who won an Oscar for her work), keeps the scare sequences moving, never letting us rest too long on one given image. But she also spends enough time with each shot to let us take in what's happening. That balance gives Jaws a certain charm when compared to today's thrillers, which cut so fast we're often completely in the dark about what's going on. Nothing turns the audience off like being kept out of the loop, and yet it seems to have become a popular movie-making trend, perhaps a cheap way to conceal mistakes from observant movie-goers. With Jaws, we're completely invested, and that ramps up the suspense even more.

I think the biggest problem I have with Jaws is how much it's been built up over the years as a classic. It's better when you don't have such grandiose expectations for it. Then you can sit back and let it entertain you. There are slow spots: the last thirty minutes get to be quite repetitive and you wish they'd just hurry up and kill the damn thing. But the big crowd scenes are well-thought-out for the most part, and there's enough energy and excitement in them to sustain you through the periodic lulls in the movie. And Scheider has great chemistry with Dreyfuss, and with Lorraine Gary, who plays his wife.

With Murray Hamilton as the mayor of Amity Island and Jeffrey Kramer as Scheider's deputy. Adapted by Carl Gottlieb and Peter Benchley from Benchley's novel. John Williams composed the now famous music score.

Tootsie

Dustin Hoffman in drag looks like Jane Fonda in Nine to Five crossed with the homicidal tranny in Dressed to Kill. Hoffman plays Michael Dorsey, a dedicated actor who gives good advice to his students (he teaches acting class to supplement his income) but fails to implement it in his own life. Michael's a has-been actor, perpetually ignored at auditions because he's too old or to young or too short or just generally "not the right fit." He waits tables while awaiting the next big part, and scolds his students for not trying to make work for themselves. (That's the one bit of advice Michael tries to follow: he's raising money to self-produce his buddy's play.) But nothing works, and even Michael's agent seems oppositional toward his career. So, in a moment of audacious desperation, he makes himself over as a woman (named Dorothy Michaels) and wins a big part on a daytime soap opera, as a gutsy hospital manager named Emily Kimberly.

The first half of the movie is just about the most inspired comedy material to come out of the 80s. That's probably because there's so much interplay between Hoffman and Bill Murray, his roommate, and Teri Garr, Michael's long-time friend and more recently, his lover. The moment you see Bill Murray you start laughing, because he has a goofy charm to him that doesn't require him to say any words. He's just naturally funny with his half-blitzed stare, as though he were possibly stoned, or possibly figuring out solutions to every problem in modern society, or both. But in some kind of alternate universe where he's content to keep it all to himself. And Teri Garr projects a marvelous frenetic energy to her role as a neurotic actress who's too self-conscious to make it past the first audition. She really comes alive, and she and Murray and Hoffman have a loose, fun chemistry together.

But the second half of the movie feels too commercial, too self-satisfied. It's a recurring problem for the director, Sydney Pollack, who also appears as Michael's agent. The year before, Pollack directed Absence of Malice, which was a proficient newspaper drama, but like Tootsie, it wasn't forceful or exciting enough to rise about its banal cleverness. Pollack seems to be the most laid-back director in recent memory (he certainly projects a likable calm as an actor, even when he's exasperated by Michael's flights of temper and petty complaints about show-business). I suppose one could take for granted that Dustin Hoffman in drag is enough force to sustain a comedy all by itself, but when it's given the 80's commercial treatment, it starts to lag. In particular, the part where Michael, as Dorothy, accompanies his co-star, Julie (Jessica Lange), to her father's house in upstate New York for the weekend. Michael lets slip his attraction for Julie, who naturally thinks that he is (as Dorothy) a lesbian. Meanwhile, Dorothy's father (Charles Durning) develops the hots for Dorothy and eventually asks her to marry him. It sounds wacky and screwball-comedyish, but in the hands of Pollack, it all seems just a notch about the melodramatic soap opera that the characters appear in. Perhaps he's trying to reign in the insanity. It's safer, more controlled, but the avoidance of risk-taking takes the edge off the comedy, and it starts to resemble a banal sitcom.

The actors really do to pull this thing off. They are, in the end, enough to make Tootsie a fun and often laugh-out-loud funny movie. It's got a lot of clever lines and a to-die-for supporting cast, which also includes Dabney Coleman as the soap's director, George Gaynes, Geena Davis, Doris Belack, and Lynne Thigpen. And above all, Tootsie is a movie about actors and acting, and more than most movies, it gives the profession its due, not only speaking to the soul-crushing rejection that so many actors face, but the endless dedication many of them put in. It also makes fun of actors, and turns the profession on its head, which keeps Tootsie from seeming like a proprietor of a bunch of self-congratulatory martyrs. And let's not forget how much fun gender confusion really is. It's an eternal source of great farce, from Shakespeare's Twelfth Night to Mrs. Doubtfire. (Even when films like Tootsie and Mrs. Doubtfire don't sustain themselves to the end, there are still pleasures to be had, like the wonderful comic performances we get from them.) 1982.

The first half of the movie is just about the most inspired comedy material to come out of the 80s. That's probably because there's so much interplay between Hoffman and Bill Murray, his roommate, and Teri Garr, Michael's long-time friend and more recently, his lover. The moment you see Bill Murray you start laughing, because he has a goofy charm to him that doesn't require him to say any words. He's just naturally funny with his half-blitzed stare, as though he were possibly stoned, or possibly figuring out solutions to every problem in modern society, or both. But in some kind of alternate universe where he's content to keep it all to himself. And Teri Garr projects a marvelous frenetic energy to her role as a neurotic actress who's too self-conscious to make it past the first audition. She really comes alive, and she and Murray and Hoffman have a loose, fun chemistry together.

But the second half of the movie feels too commercial, too self-satisfied. It's a recurring problem for the director, Sydney Pollack, who also appears as Michael's agent. The year before, Pollack directed Absence of Malice, which was a proficient newspaper drama, but like Tootsie, it wasn't forceful or exciting enough to rise about its banal cleverness. Pollack seems to be the most laid-back director in recent memory (he certainly projects a likable calm as an actor, even when he's exasperated by Michael's flights of temper and petty complaints about show-business). I suppose one could take for granted that Dustin Hoffman in drag is enough force to sustain a comedy all by itself, but when it's given the 80's commercial treatment, it starts to lag. In particular, the part where Michael, as Dorothy, accompanies his co-star, Julie (Jessica Lange), to her father's house in upstate New York for the weekend. Michael lets slip his attraction for Julie, who naturally thinks that he is (as Dorothy) a lesbian. Meanwhile, Dorothy's father (Charles Durning) develops the hots for Dorothy and eventually asks her to marry him. It sounds wacky and screwball-comedyish, but in the hands of Pollack, it all seems just a notch about the melodramatic soap opera that the characters appear in. Perhaps he's trying to reign in the insanity. It's safer, more controlled, but the avoidance of risk-taking takes the edge off the comedy, and it starts to resemble a banal sitcom.

The actors really do to pull this thing off. They are, in the end, enough to make Tootsie a fun and often laugh-out-loud funny movie. It's got a lot of clever lines and a to-die-for supporting cast, which also includes Dabney Coleman as the soap's director, George Gaynes, Geena Davis, Doris Belack, and Lynne Thigpen. And above all, Tootsie is a movie about actors and acting, and more than most movies, it gives the profession its due, not only speaking to the soul-crushing rejection that so many actors face, but the endless dedication many of them put in. It also makes fun of actors, and turns the profession on its head, which keeps Tootsie from seeming like a proprietor of a bunch of self-congratulatory martyrs. And let's not forget how much fun gender confusion really is. It's an eternal source of great farce, from Shakespeare's Twelfth Night to Mrs. Doubtfire. (Even when films like Tootsie and Mrs. Doubtfire don't sustain themselves to the end, there are still pleasures to be had, like the wonderful comic performances we get from them.) 1982.

July 19, 2012

Orange County

Orange County (2002) isn't offensive, exactly, but it isn't a very good movie, either. It's about an aspiring writer named Shaun (Colin Hanks), who's convinced that he needs to go to Stanford and study with a writer he's stuck on. The movie is about the various misadventures that take place in one 24-hour period during which Shaun tries to get accepted, after the dippy college counselor at his high school (Lily Tomlin in a bit role) sends in the wrong transcript and he gets rejected. That's an interesting idea, but the writer of Orange County, Mike White (who plays a small role as Shaun's English teacher), is running on empty from the very beginning.

The earnest performance of Colin Hanks (son of Tom Hanks) is one of this movie's strongest attributes, yet the writing is so undeveloped that you never really buy his whole aspiring-literary-talent thing. He's a nice guy. That's about all we get. We see him transform from stoned surfer to would-be Ernest Hemingway, but there's no real impetus for his transformation, other than the sudden death of one of his surfing buddies, an obvious plot device. And if you're paying any attention at all to the movie, you'll see how many of these plot devices White relies on in his script. For example, Shaun's brother, Lance (played by Jack Black), is a ne'er-do-well junkie who's mooching off his family, and it's his stupid behavior that bungles a meeting between Shaun and an influential Stanford board member. Later, it's Lance who sets up an astoundingly contrived chain of events that gets Shaun into the school.

This movie doesn't know how to show its feelings, such as disappointment, frustration, grief, or joy, and so it turns to catchy pop songs to convey its emotions by proxy. Is it any wonder that a movie produced by a music conglomerate like MTV fails in its grasp for authenticity? You start to think they just made it so they could sell the soundtrack. Perhaps the audience saw through this: Orange County wasn't exactly a hit.

There's a slew of talent associated with the film, but don't expect much when the material is this sloppy. Director Jake Kasdan (who helmed last year's abysmal Bad Teacher) has a sitcom-level mentality, and he doesn't know how to work with the actors. They're all emotionally maxed-out characters at the beginning, and so there's nowhere for them to go emotionally. They fizzle. Catherine O'Hara has a few good moments as Shaun's drunk mother, but even she isn't allowed to reach her wonderfully loony potential. (She does some similar (but better) work in an episode of HBO's Curb Your Enthusiasm.) Kevin Kline puts in a brief spot as the idolized writer, whose appearance marks the film's climax, but he's reduced to the role of the "wise artiste," providing Shaun (and the movie) with some tripe about writing. When you see a performer like Kevin Kline playing such a boring role, it gives you little hope for the future of comedy in movies. Also present are John Lithgow as Shaun's dad, Chevy Chase as the high school principal, Brett Harrison and Kyle Howard as Shaun's perpetually stoned surfer buddies, and Schuyler Fisk (daughter of Sissy Spacek) as Shaun's good-natured girlfriend, the only sane person in his life. And Jack Black, who is an often dizzying force of energy, is all over the place with his mugging. (There are too many stoners in this movie for any of them to stand out, for one thing.) He needs a good director to channel his crazed brilliance. Without that, he's utterly unfunny.

The really ironic thing is that Orange County presents the adults as complete morons: the guidance counselor's gaffe generates the entire meandering plot, the parents are miserable, clinging people. They're divorced from each other and both in unhappy, unsuccessful re-marriages (for all the wrong reasons). The teachers are either stupid or disingenuous (or both). And yet, we're expected to believe that Shaun turned into a sophisticated, responsible young man amidst all this incompetency. And to top it off [SPOILER ALERT], the movie has the nerve to go Frank Capra on us at the end: Mom and Dad get back together, Son gets into Stanford via their generous financial donation to the school, he decides that home really is where the heart is, and we're all happily-ever-after-together. [END OF SPOILERS.] It's amazing that such an essentially square movie could come from the people at MTV, who seem so convinced that they are the purveyors of what's hip. Perhaps they're turning over a new leaf. They've learned that banality is safer than originality. Oh wait, that's not a new concept to them at all.

With Harold Ramis as the dean of admissions, Garry Marshall, Dana Ivey, Jane Adams, and Ben Stiller in an undistinguished cameo appearance as a firefighter.

The earnest performance of Colin Hanks (son of Tom Hanks) is one of this movie's strongest attributes, yet the writing is so undeveloped that you never really buy his whole aspiring-literary-talent thing. He's a nice guy. That's about all we get. We see him transform from stoned surfer to would-be Ernest Hemingway, but there's no real impetus for his transformation, other than the sudden death of one of his surfing buddies, an obvious plot device. And if you're paying any attention at all to the movie, you'll see how many of these plot devices White relies on in his script. For example, Shaun's brother, Lance (played by Jack Black), is a ne'er-do-well junkie who's mooching off his family, and it's his stupid behavior that bungles a meeting between Shaun and an influential Stanford board member. Later, it's Lance who sets up an astoundingly contrived chain of events that gets Shaun into the school.

This movie doesn't know how to show its feelings, such as disappointment, frustration, grief, or joy, and so it turns to catchy pop songs to convey its emotions by proxy. Is it any wonder that a movie produced by a music conglomerate like MTV fails in its grasp for authenticity? You start to think they just made it so they could sell the soundtrack. Perhaps the audience saw through this: Orange County wasn't exactly a hit.

There's a slew of talent associated with the film, but don't expect much when the material is this sloppy. Director Jake Kasdan (who helmed last year's abysmal Bad Teacher) has a sitcom-level mentality, and he doesn't know how to work with the actors. They're all emotionally maxed-out characters at the beginning, and so there's nowhere for them to go emotionally. They fizzle. Catherine O'Hara has a few good moments as Shaun's drunk mother, but even she isn't allowed to reach her wonderfully loony potential. (She does some similar (but better) work in an episode of HBO's Curb Your Enthusiasm.) Kevin Kline puts in a brief spot as the idolized writer, whose appearance marks the film's climax, but he's reduced to the role of the "wise artiste," providing Shaun (and the movie) with some tripe about writing. When you see a performer like Kevin Kline playing such a boring role, it gives you little hope for the future of comedy in movies. Also present are John Lithgow as Shaun's dad, Chevy Chase as the high school principal, Brett Harrison and Kyle Howard as Shaun's perpetually stoned surfer buddies, and Schuyler Fisk (daughter of Sissy Spacek) as Shaun's good-natured girlfriend, the only sane person in his life. And Jack Black, who is an often dizzying force of energy, is all over the place with his mugging. (There are too many stoners in this movie for any of them to stand out, for one thing.) He needs a good director to channel his crazed brilliance. Without that, he's utterly unfunny.

The really ironic thing is that Orange County presents the adults as complete morons: the guidance counselor's gaffe generates the entire meandering plot, the parents are miserable, clinging people. They're divorced from each other and both in unhappy, unsuccessful re-marriages (for all the wrong reasons). The teachers are either stupid or disingenuous (or both). And yet, we're expected to believe that Shaun turned into a sophisticated, responsible young man amidst all this incompetency. And to top it off [SPOILER ALERT], the movie has the nerve to go Frank Capra on us at the end: Mom and Dad get back together, Son gets into Stanford via their generous financial donation to the school, he decides that home really is where the heart is, and we're all happily-ever-after-together. [END OF SPOILERS.] It's amazing that such an essentially square movie could come from the people at MTV, who seem so convinced that they are the purveyors of what's hip. Perhaps they're turning over a new leaf. They've learned that banality is safer than originality. Oh wait, that's not a new concept to them at all.

With Harold Ramis as the dean of admissions, Garry Marshall, Dana Ivey, Jane Adams, and Ben Stiller in an undistinguished cameo appearance as a firefighter.

July 18, 2012

Blue Velvet

Writer-director David Lynch's Blue Velvet (1986) exists in a suburban vacuum that's some kind of tangled 1950s-1980s dream. Lynch takes a highly normal suburban boyhood fantasy, becoming involved in a real-life mystery, and throws it into the depths of sordidness. It's almost too enticing to witness the undressing of suburbia, a place that is so squeaky clean on the outside it almost has to be a den of devils on the inside. Kyle MacLachlan plays the hero, Jeffrey, who discovers a severed human ear while walking through a field near his quiet Lumberton hometown, a place that recalls every falsely cheerful family sitcom ever made.

Jeffrey wastes no time in delivering the ear to the local police, but this effectively ends his ability to partake in the mystery legally, so, with the help of the detective's teenage daughter, Sandy (Laura Dern), he proceeds with his own makeshift investigation and sneaks into the apartment of a lounge singer (Isabella Rossellini), whose name Sandy has heard mentioned in connection with the ongoing investigation of the detached ear. The lounge singer is named Dorothy Vallens, and she's about as stable as Judy Garland. She has that tragic look, mixed with a distinctively foreign allure that makes her suspect to our suburbanite values and beliefs. (Rossellini is the daughter of Ingrid Bergman, and you can hear it in her voice and see it in her face.)

Enter Dennis Hopper as Frank, the psychotic, drug-addicted, sadomasochist who's forcing Dorothy to comply with his weird fetishistic fantasies. Frank's got to be one of the scariest human figures in horror-thriller movie history, on par with Robert Mitchum's Reverend Harry Powell in Night of the Hunter and Jack Nicholson's nutcase hotel sitter in The Shining. This is the point in the movie where Jeffrey is probably thinking that "normal" isn't so bad, and that those mysteries we read about as children and watched on television and at the movies were deliciously entertaining because they were false, safe mysteries where even the worst villains conducted themselves within reasonable boundaries. Dennis Hopper has no boundaries, nor does the director, who puts us in the position of the peeping tom and the "peeped-upon," on a far more visceral and uncomfortable level than say, Hitchcock did, in his Rear Window.

The thing about Blue Velvet is that it's an off-putting descent into a frightening suburban reality, because it breaks through the surface in others that we often feel superior to, and in the process, it exposes our own carefully constructed phoniness as an obviously thin veneer. Sandy says to Jeffrey, "I don't know whether you're a detective or a pervert," after he tells her of his plan to infiltrate Dorothy's apartment for the first time. He tells her with false coyness that she'll just have to find out. What he really means is that he'll just have to find out, because he doesn't know himself well enough to know what he really wants, why he's really attracted to the "mystery". For him, "mystery" is still a gimmick designed primarily for his own amusement, not something that involves or affects real people. It lulls him in with the siren song of the false mysteries (the camera occasionally shows us shots of various 1940s film noirs on the TV screen, a reminder of the ground we're treading, which is quite far away from the mock-sophisticated safety of Hollywood). In David Lynch territory, nothing is ever safe and neat and tidy. But it's not a pleasurable entertainment. It's on the level of a snuff movie, and for all its ironic insights into human nature and the phoniness of the world it portrays, it's hard to watch.

With Dean Stockwell, Hope Lange, George Dickerson, Priscilla Pointer, Frances Bay, and Brad Dourif.

Jeffrey wastes no time in delivering the ear to the local police, but this effectively ends his ability to partake in the mystery legally, so, with the help of the detective's teenage daughter, Sandy (Laura Dern), he proceeds with his own makeshift investigation and sneaks into the apartment of a lounge singer (Isabella Rossellini), whose name Sandy has heard mentioned in connection with the ongoing investigation of the detached ear. The lounge singer is named Dorothy Vallens, and she's about as stable as Judy Garland. She has that tragic look, mixed with a distinctively foreign allure that makes her suspect to our suburbanite values and beliefs. (Rossellini is the daughter of Ingrid Bergman, and you can hear it in her voice and see it in her face.)

Enter Dennis Hopper as Frank, the psychotic, drug-addicted, sadomasochist who's forcing Dorothy to comply with his weird fetishistic fantasies. Frank's got to be one of the scariest human figures in horror-thriller movie history, on par with Robert Mitchum's Reverend Harry Powell in Night of the Hunter and Jack Nicholson's nutcase hotel sitter in The Shining. This is the point in the movie where Jeffrey is probably thinking that "normal" isn't so bad, and that those mysteries we read about as children and watched on television and at the movies were deliciously entertaining because they were false, safe mysteries where even the worst villains conducted themselves within reasonable boundaries. Dennis Hopper has no boundaries, nor does the director, who puts us in the position of the peeping tom and the "peeped-upon," on a far more visceral and uncomfortable level than say, Hitchcock did, in his Rear Window.

The thing about Blue Velvet is that it's an off-putting descent into a frightening suburban reality, because it breaks through the surface in others that we often feel superior to, and in the process, it exposes our own carefully constructed phoniness as an obviously thin veneer. Sandy says to Jeffrey, "I don't know whether you're a detective or a pervert," after he tells her of his plan to infiltrate Dorothy's apartment for the first time. He tells her with false coyness that she'll just have to find out. What he really means is that he'll just have to find out, because he doesn't know himself well enough to know what he really wants, why he's really attracted to the "mystery". For him, "mystery" is still a gimmick designed primarily for his own amusement, not something that involves or affects real people. It lulls him in with the siren song of the false mysteries (the camera occasionally shows us shots of various 1940s film noirs on the TV screen, a reminder of the ground we're treading, which is quite far away from the mock-sophisticated safety of Hollywood). In David Lynch territory, nothing is ever safe and neat and tidy. But it's not a pleasurable entertainment. It's on the level of a snuff movie, and for all its ironic insights into human nature and the phoniness of the world it portrays, it's hard to watch.

With Dean Stockwell, Hope Lange, George Dickerson, Priscilla Pointer, Frances Bay, and Brad Dourif.

July 17, 2012

Slap Shot

Paul Newman plays an aging hockey star who tries to save his languishing team, the Chiefs, by turning the games into sideshows, full of violent fight scenes. It works: the has-been Chiefs re-invent the sport's appeal with their apish antics. Newman sells the material, but it's still not sustainable for two hours. Slap Shot is lewd and loud and full of people behaving violently "funny," and it's amusing seeing Newman in what is probably his dirtiest movie role, but the results are uneven. You laugh a little, but in between the sporadic bits of comedy that really work is a movie that tries way too hard. It's often dull and uninvolving. George Roy Hill's laid-back directing style doesn't do the film any favors. The finale is admittedly wonderfully irreverent, making fun of the macho jock mentality of sports, the public, everybody. Written by Nancy Dowd. Michael Ontkean makes a promising debut (not his first movie, but his first big movie role) as one of Newman's fellow players, who's turned off by all the publicity mongering, and Strother Martin has some funny moments as the team's manager. With Melinda Dillon, Lindsay Crouse as Ontkean's wife, Jennifer Warren as Newman's wife, Jerry Houser, Andrew Duncan, Swoosie Kurtz, and M. Emmet Walsh. 1977.

July 16, 2012

The Godfather Part II

In the first Godfather, Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) never believed he could be sucked into his father's way of doing things. And in The Godfather Part II (1974), he can't accept that he has. His corruption happens quickly but subtly. Under the guise of vengeance, of protecting family honor, Michael becomes a tragic fallen hero. Director Francis Ford Coppola and author Mario Puzo have created a sequel that fills in a lot of detail for us, simultaneously depicting Michael's rise as the new Don Corleone and the life of young Vito (played in flashback by Robert De Niro) as he leaves Sicily for America and gradually begins a life of crime.

There are moments of greatness in The Godfather Part II, and moments of great drama. Some of the images stay with you, and considering how much it attempts, much of this movie is a smashing success. The actors are exceedingly good: Pacino shines darkly. You can see the transformation he's undergone in his face, which was once innocent. Now it has a yellow patina of greed and an addiction to power. Diane Keaton gets some stronger material in this sequel as well. She's the good wife who's stuck by Michael for longer than she should have, who's looked the other way too many times now. De Niro is a solid Vito (it's no small feat filling the shoes of Marlon Brando), Talia Shire adds a new level of depth to Connie, Michael's sister, who was always getting roughed up by her sleazy husband Carlo in the first one. In Part II she's given herself over to money and things, at the expense of her family. But then she experiences something of a reversal of character, and she rises up to be the family's new matriarch. It's fascinating to watch all these performances and the depths to which the actors take them.

But it's lacking something. Many critics have proclaimed this an even better film than its predecessor. They praise it for deepening the material, for elevating it to a mythological status. It's just that in the process of demonstrating how far Michael has fallen, the movie too seems to lose its soul. Despite the fact that he had already been corrupted by the end of the first Godfather, that film left you with a sense of ambiguity. That perhaps things were going to be different. After all, Michael's involvement in murder had been about "vengeance" and "justice." But in the sequel, we start to see the consequences of that. It's beautiful and compelling yet bleak and depressing. And the powerful scenes are linked by many scenes that lumber along. (It's three hours and twenty minutes long, where the first was under three, a significant difference.) The tacked-on ending, a flashback of the days before WW2, when all the children were alive, but grown, feels too TV-movie-ish, like Coppola was already showing signs of the bad judgment that would taint his directing ever after. (It is nice to see James Caan reprising his role as Sonny, if ever so briefly. His absence is really felt--Sonny was such a presence, such an iconic character, and Caan turned him into a hot-headed bad boy who you liked because of his brashness and his macho love for his family.)

Part II deserves credit for what it does and what it is: a very good movie, and a compelling study of the soul-destroying power of an America that has built-in methods of abiding criminal activity. It also gets at the things which knit this family together, and the myriad forces which tear it apart. With Robert Duvall, John Cazale, Lee Strasberg, Michael Gazzo, G.D. Spradlin, Richard Bright, Bruno Kirby, Morgana King, and Gianni Russo.

There are moments of greatness in The Godfather Part II, and moments of great drama. Some of the images stay with you, and considering how much it attempts, much of this movie is a smashing success. The actors are exceedingly good: Pacino shines darkly. You can see the transformation he's undergone in his face, which was once innocent. Now it has a yellow patina of greed and an addiction to power. Diane Keaton gets some stronger material in this sequel as well. She's the good wife who's stuck by Michael for longer than she should have, who's looked the other way too many times now. De Niro is a solid Vito (it's no small feat filling the shoes of Marlon Brando), Talia Shire adds a new level of depth to Connie, Michael's sister, who was always getting roughed up by her sleazy husband Carlo in the first one. In Part II she's given herself over to money and things, at the expense of her family. But then she experiences something of a reversal of character, and she rises up to be the family's new matriarch. It's fascinating to watch all these performances and the depths to which the actors take them.

But it's lacking something. Many critics have proclaimed this an even better film than its predecessor. They praise it for deepening the material, for elevating it to a mythological status. It's just that in the process of demonstrating how far Michael has fallen, the movie too seems to lose its soul. Despite the fact that he had already been corrupted by the end of the first Godfather, that film left you with a sense of ambiguity. That perhaps things were going to be different. After all, Michael's involvement in murder had been about "vengeance" and "justice." But in the sequel, we start to see the consequences of that. It's beautiful and compelling yet bleak and depressing. And the powerful scenes are linked by many scenes that lumber along. (It's three hours and twenty minutes long, where the first was under three, a significant difference.) The tacked-on ending, a flashback of the days before WW2, when all the children were alive, but grown, feels too TV-movie-ish, like Coppola was already showing signs of the bad judgment that would taint his directing ever after. (It is nice to see James Caan reprising his role as Sonny, if ever so briefly. His absence is really felt--Sonny was such a presence, such an iconic character, and Caan turned him into a hot-headed bad boy who you liked because of his brashness and his macho love for his family.)

Part II deserves credit for what it does and what it is: a very good movie, and a compelling study of the soul-destroying power of an America that has built-in methods of abiding criminal activity. It also gets at the things which knit this family together, and the myriad forces which tear it apart. With Robert Duvall, John Cazale, Lee Strasberg, Michael Gazzo, G.D. Spradlin, Richard Bright, Bruno Kirby, Morgana King, and Gianni Russo.

Days of Heaven

The story isn’t bad, but Malick wants the nature imagery to envelop it (and us). He enjoys de-emphasizing human stories in favor of natural imagery. (He's almost righteously anti-plot, which may explain why he uses such a tired one. We’ve already seen it before, and Malick prefers that we fill in all the gaps for ourselves, with bits of dialogue and parts of other movies we’ve seen. That way Malick can focus on art.) Like 2011’s The Tree of Life, Days of Heaven isn’t terrible, necessarily, and there are certain images that remain in your head, particularly the scene where locusts invade the wheat fields. But it all boils down to something pretentiously antithetical to the enjoyment of movies, as much as it tries for some kind of vapid “pure cinema” look and feel. The worst part is that so many people have been fooled into thinking it's great cinema. It's technically well-made, but it's difficult to respond to the characters when they feel so muted, so undernourished, as though their own creator had nothing but contempt--or worse, disinterest, which grows out of contempt--for them. Linda Manz plays Gere’s kid-sister, who narrates the film with her distractingly ugly New York accent. Malick wants her childish observations to sound philosophical, but they’re really just cant.

The Godfather

Even those who haven't seen The Godfather (1972) are aware of its status as one of the all-time great motion pictures of our time. Some critics refer to it as the Gone With the Wind of the 1970s. A good many people consider it the greatest film of all time, or at the very least, somewhere in the top five. It may be worthwhile to venture back into film history for a few moments, to help those movie-goers who aren't familiar with the movie and its significance, understand why there's still so much hoopla.

First off, movies about organized crime are about as old as the medium itself. Scarface (1932) is one noteworthy example from among the early talkies. Many of these old-school crime flicks concerned themselves with Prohibition, and the licentious pleasures associated with that era of government-mandated morality. These movies are one of the reasons film has always been a sort of prodigal medium: an art form for the common people, the mass audience, concerned with iniquities and people of dubious character. That's the appeal of movies, ultimately. They're not good for us. (The Novel, when it was in vogue, was also considered suspect, denounced as the art of the "common," and what's more, as a medium full of subversive potential. As they say, the movies are the 20th century's answer to the Novel. Both have received similar treatment. But we've become post-literate, and one wonders if the same will happen to movies in the 21st century, ushering in a post-cinematic public.)

The appeal of such entertaining movies was threatened with the production codes starting in the mid-30s, which set strict rules about what films could depict in terms of sex and violence, etc. The major studios mostly churned out sanitized material that was non-threatening and "safe" and "clean." Writers and directors who wanted to address adult subject matter had to be coy about it, or risk being censored by the studio heads. Film adaptations of novels and plays had to tone down racy material. For example, when Tennessee Williams' play Cat on a Hot Tin Roof was made into an MGM movie, the main character's homosexuality was removed from the story. Those familiar with the source material of such expurgated movie adaptations could read between the lines, sure, but it would seem that studios exercised a great deal of confidence in the ignorance of the movie-going public at large. Moreover, they perpetuated such ignorance by depicting life in a blissful state. It's like the men in The Stepford Wives (1975) who want to pretend their wives haven't been turned into automatons. Sure, there have always been exceptions to this rule, but mostly Hollywood was about keeping things superficial and fake.

Then came the 1960s. Films like Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless (1960) in France and Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde (1967) in America began to introduce a new kind of realism to the movie-going public, a violent realism that re-examined the values of movies and ignited a new passion for something different, something urgently real.

Along the heals of Bonnie and Clyde and The Wild Bunch (1969) and other such movies came The Godfather. What people tend to see in The Godfather is a sort of tragic humanization of these old-time gangsters, once cartoonish, expendable, forgotten the moment the picture was finished. In this new vision of the American organized crime world, these characters are no longer divorced from their human context. They are fathers and sons and brothers and husbands, and they bleed real blood. They are corrupt, but also redeemable. They have scruples, as antithetical as that may sound, and their own moral code, which too seems incredulous, and yet they are cold-blooded killers. Ambiguity is always more interesting than morality depicted in black-and-white.

But enough about film context. You can read all that elsewhere, and it doesn't mean you have to like The Godfather a bit. The movie speaks for itself. (The context may deepen one's understanding, but it does not define it.) Marlon Brando plays the head of the Corleone family, based in New York (it starts in 1945, just after the war has ended), who's competing with several other crime families. A chain of events, beginning with Don Corleone's rejection of a narcotics operation in conjunction with the other families, sets up his youngest son, Michael (Al Pacino) to take over the family business, neither a vocation nor a lifestyle he wanted. He's the war hero, the "pure" son, untainted by the blood of organized crime. (They were going to try and land him a political career so he could be "untainted" there too.) It's inevitable of course that Michael is sucked into the world he thought he was too principled to embrace.

Director Francis Ford Coppola turns this gangster picture into a tragic masterpiece. He is helped by Mario Puzo, on whose novel this was based, and with whom he wrote the screenplay. The iconic music is by Nino Rota. The supporting cast includes James Caan as Sonny, Robert Duvall as Tom Hagen, Richard Castellano as Clemenza, Diane Keaton as Kay, Michael's wife, Talia Shire as Connie, John Cazale as Fredo. Also starring Abe Vigoda, Al Littieri, Gianni Russo, Sterling Hayden, Lenny Montana, Richard Conte, Al Martino, John Marley, Alex Rocco, and Morgana King. Followed by two sequels. (The only criticism I can give of The Godfather is that it spawned a lot of inferior imitations that we have had to sit through for the last 40 years.)

First off, movies about organized crime are about as old as the medium itself. Scarface (1932) is one noteworthy example from among the early talkies. Many of these old-school crime flicks concerned themselves with Prohibition, and the licentious pleasures associated with that era of government-mandated morality. These movies are one of the reasons film has always been a sort of prodigal medium: an art form for the common people, the mass audience, concerned with iniquities and people of dubious character. That's the appeal of movies, ultimately. They're not good for us. (The Novel, when it was in vogue, was also considered suspect, denounced as the art of the "common," and what's more, as a medium full of subversive potential. As they say, the movies are the 20th century's answer to the Novel. Both have received similar treatment. But we've become post-literate, and one wonders if the same will happen to movies in the 21st century, ushering in a post-cinematic public.)

The appeal of such entertaining movies was threatened with the production codes starting in the mid-30s, which set strict rules about what films could depict in terms of sex and violence, etc. The major studios mostly churned out sanitized material that was non-threatening and "safe" and "clean." Writers and directors who wanted to address adult subject matter had to be coy about it, or risk being censored by the studio heads. Film adaptations of novels and plays had to tone down racy material. For example, when Tennessee Williams' play Cat on a Hot Tin Roof was made into an MGM movie, the main character's homosexuality was removed from the story. Those familiar with the source material of such expurgated movie adaptations could read between the lines, sure, but it would seem that studios exercised a great deal of confidence in the ignorance of the movie-going public at large. Moreover, they perpetuated such ignorance by depicting life in a blissful state. It's like the men in The Stepford Wives (1975) who want to pretend their wives haven't been turned into automatons. Sure, there have always been exceptions to this rule, but mostly Hollywood was about keeping things superficial and fake.

Then came the 1960s. Films like Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless (1960) in France and Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde (1967) in America began to introduce a new kind of realism to the movie-going public, a violent realism that re-examined the values of movies and ignited a new passion for something different, something urgently real.

Along the heals of Bonnie and Clyde and The Wild Bunch (1969) and other such movies came The Godfather. What people tend to see in The Godfather is a sort of tragic humanization of these old-time gangsters, once cartoonish, expendable, forgotten the moment the picture was finished. In this new vision of the American organized crime world, these characters are no longer divorced from their human context. They are fathers and sons and brothers and husbands, and they bleed real blood. They are corrupt, but also redeemable. They have scruples, as antithetical as that may sound, and their own moral code, which too seems incredulous, and yet they are cold-blooded killers. Ambiguity is always more interesting than morality depicted in black-and-white.

But enough about film context. You can read all that elsewhere, and it doesn't mean you have to like The Godfather a bit. The movie speaks for itself. (The context may deepen one's understanding, but it does not define it.) Marlon Brando plays the head of the Corleone family, based in New York (it starts in 1945, just after the war has ended), who's competing with several other crime families. A chain of events, beginning with Don Corleone's rejection of a narcotics operation in conjunction with the other families, sets up his youngest son, Michael (Al Pacino) to take over the family business, neither a vocation nor a lifestyle he wanted. He's the war hero, the "pure" son, untainted by the blood of organized crime. (They were going to try and land him a political career so he could be "untainted" there too.) It's inevitable of course that Michael is sucked into the world he thought he was too principled to embrace.

Director Francis Ford Coppola turns this gangster picture into a tragic masterpiece. He is helped by Mario Puzo, on whose novel this was based, and with whom he wrote the screenplay. The iconic music is by Nino Rota. The supporting cast includes James Caan as Sonny, Robert Duvall as Tom Hagen, Richard Castellano as Clemenza, Diane Keaton as Kay, Michael's wife, Talia Shire as Connie, John Cazale as Fredo. Also starring Abe Vigoda, Al Littieri, Gianni Russo, Sterling Hayden, Lenny Montana, Richard Conte, Al Martino, John Marley, Alex Rocco, and Morgana King. Followed by two sequels. (The only criticism I can give of The Godfather is that it spawned a lot of inferior imitations that we have had to sit through for the last 40 years.)

July 14, 2012

A Fish Called Wanda

A Fish Called Wanda is a throwback to screwball comedies, directed by Charles Crichton, a veteran of English comedies from the 40s and 50s, and co-written by Crichton and Monty Python's John Cleese. It's a heist movie with Cleese as an English barrister who becomes romantically involved with a sexy American con artist named Wanda, played by Jamie Lee Curtis, and her live-wire "brother" Otto (Kevin Kline). They're in cahoots with a bank robber, George (Tom Georgeson), whom Cleese is defending. (They turned him in to the police with hopes of making off with the loot, unaware that George had spirited it away beforehand.)

John Cleese successfully convinces us that he's capable of being a romantic lead as the married, dulled-out lawyer Archie Leach, and Jamie Lee Curtis does some of her best work as Wanda. She's playful and smart, and a born performer (or a ham is more like it). Loony comedy suits her talent and her looks well, and this intermingling of British and American styles of humor seems to bring out the best in her, as it does for Cleese. But it's Kevin Kline as Otto who really breaks out of the mold, delivering an off-the-wall performance as a macho moron who reads Nietzsche but hasn't a clue what it means. Otto can't stand being insulted, particularly when it comes to his "intelligence," and he makes up for his insecurities in the typical male fashion: with violent, aggressive fervor. He's hysterical, and even won an Academy Award, which rarely happens for comedic performances (or comedic anything for that matter.)

As a movie, A Fish Called Wanda sags in parts, but it makes up for its slow spots and its indulgences by being a deliriously bawdy British-American spectacle, one that's perhaps trying too hard to one-up American comedies in terms of its proud vulgarity. (It's always more clever than a truly vulgar movie, though.) You spend a lot of the time giggling at its crude humor, when you're not laughing at the genuinely fun and earnest comic performances. And there are some particularly brilliant scenes, like the one where Archie's wife (Maria Aitken) unexpectedly returns home when Archie and Wanda are kissing on the sofa. Otto, always the jealous type and never subtle, is also inside, watching, and he tries to save Archie from being found out, displaying his inability to make up a believable story to Archie's wife, who sees through him. Kline is fast with the insults, though, and he completely throws himself into his character's manic personality. The energy in some of the scenes of this movie is wonderful stuff, a real novelty in the 80s, where so many comedies seemed too carefully planned out. The best scenes in Wanda are remarkably off-the-cuff, and yet they don't seem sloppy or unstructured. They have the panache and style of good writing and the zing of good improvisation.

Michael Palin, another Monty Python regular, co-stars as Ken, one of the accomplices in the bank robbery scheme that quickly becomes subordinate to the romantic story and this film's garish insanity. The cast reunited for 1996's Fierce Creatures, which wasn't as tight or as clever as Wanda. 1988.