Below are short reviews of movies I never got around to writing about.

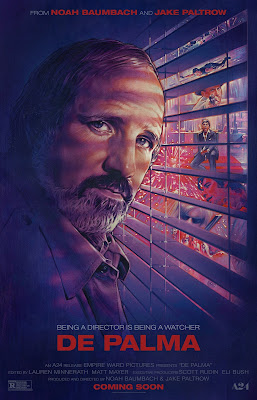

De Palma. Legendary filmmaker Brian De Palma (Carrie, Scarface, The Untouchables) sits down and gabs for 100 minutes about his career: the early days of the 1960s, making anti-establishment films and working with De Niro, the 70s, when he was at his peak as a filmmaker and working alongside Spielberg, Scorsese, Coppola, and others during the most exciting period in American films, the shift his career took in the 80s, including some of his biggest successes (e.g. The Untouchables) and most humiliating disappointments (The Bonfire of the Vanities). De Palma also talks about other directors, including Hitchcock, a major influence on his work, and gives us a sense of how a director can truly be an artist, or how the corporate nature of Hollywood can destroy a director’s vision. Of course, it’s all coming from De Palma himself, a man who’s honest but not a little arrogant (a character trait we expect from great Hollywood directors). I’d love to see a sequel with actors, producers, writers, and crew members discussing De Palma. This movie’s a delight for any film lover, and you can rent it on iTunes.

Florence Foster Jenkins. Meryl Streep, playing the insane, syphilitic Florence (a woman who thought she could sing, and since she was rich and crazy, was allowed to), warbles and croons her way to Carnegie Hall. We could almost suspect that Darling Streep was making fun of herself, if it weren’t for the fact that she treats even this role like a dissertation. She’s done her homework, studied the most accurate and realistic way to be a terrible singer and a happy loon. Somehow, a studied performance of this kind rings false, and Florence Foster Jenkins isn’t good, but isn’t bad enough to be really amusing as a failure. It’s just Streep being artfully ridiculous, and suddenly, Ricki and the Flash doesn’t seem all that bad.

The Handmaiden. Park Chan-Wook’s mesmerizingly produced but cold adaptation of Fingersmith, the trendy neo-Victorian thriller by Sarah Waters. The cinema police have declared it a masterpiece, because it is beautifully made, with many exciting shots and an elaborate and impressive production design by Seong-hie Ryu. But as beautifully hip as The Handmaiden is, the film never grabbed me. The story involves an impoverished girl named Sook-hee who becomes embroiled in a scheming young cad’s plot to marry a naive rich girl for her money. But there are plot twists upon plot twists, as there are in Waters’ novel. (The film is mostly faithful, except of course that it updates the setting from 19th-century London to early 20th century Japan). But Waters’ writing has always turned me off: she’s aping the Victorian style in a calculated way, and imposing her modern-day literary sensibility (one I find mostly unreadable) on the sensation fiction that was popular at the time, much of which was delightfully disposable. But with Waters, every word is steeped in meaning, like tea that’s become impossible to drink. The Handmaiden makes the same mistake: every object has been deified, and we’re suddenly not lost in a movie but trapped in a museum, with a numbing feeling that we’re supposed to be having a good time.

The Love Witch. Anna Biller’s throwback to 1960s B movies and Technicolor (it was filmed on 35mm), laced with a little psychedelic occultism and some kind of anti-feminist feminism, in which Samantha Robinson plays Elaine, a self-described witch who’s got a yen for men, but can’t seem to keep them alive. It’s those love potions she keeps making in her witchy bachelorette pad in a big, gabled Victorian house that looks like the one Mary Richards lived in, if Mary Richards had been a spell-casting nymphomaniac. (And who knows what Mary did on her off-days.) When the film opens, we see Samantha driving in her convertible along the Pacific Coast highway, and it feels like an old movie just blew us a kiss from Cinema Heaven. The Love Witch goes on for two full hours, which is too long (the movies it imitates were all like an hour and some change), but it’s a canny, fun, strange, at times hilarious movie about women consumed with their need to be loved. When Elaine and her boyfriend—a strapping detective named Griff—are walking in the woods and stumble across some kind of traveling Medieval circus run by Elaine’s occultist friends, I’m reminded that we should never lose hope in the movies if somewhere, Anna Biller can make a movie as deliriously nutty as this one.

Sing Street. John Carney, director of the 2007 musical Once, offers another music-obsessed film, in which a group of high school boys form a band called ‘Sing Street’ (named after their oppressive Catholic secondary school). It’s set in the 1980s in the wake of MTV, and Conor (Ferdia Walsh-Peelo), who’s never really been interested in making music (unlike his older brother Brendan, a has-been college-dropout, played with heart by Jack Reynor), takes a liking for a beautiful young model named Raphina (Lucy Boynton). (This movie, incidentally, is the first time I've seen a defense of MTV as the purveyor of a new art form, the music video, rather than the death knell of rock 'n' roll.) The band is his attempt to impress her. But when he teams up with Eamon (Mark McKenna), a musical prodigy who wears big glasses like John Lennon, the band becomes more than just an after-thought. Sing Street has its flaws (when the boys seek out the only black kid in their school because they assume he’s musical, they’re right, and they welcome him into the band, but the movie never fleshes out his character, which makes their tokenism John Carney’s tokenism). But what I love about Sing Street is its exuberant love of its characters and its reminder of why people first fall in love with the creative process: it’s a way to express our rage at the world. And who could resist a movie that channels its rage into something as charming and fun as this?

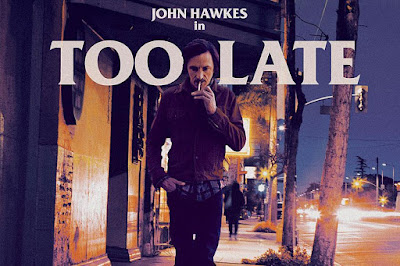

Too Late. A disappointing L.A. noir starring John Hawkes as a private eye looking for a missing girl. The film plays around with time and narrative, acting like a Modernist novel, and reveals its big plot points early and then shows us how those things happened. Writer-director Dennis Huack shows some promise as a filmmaker: he clearly has a vision and a desire to subvert genres, but he’s maybe too influenced by the likes of Quentin Tarantino and other “hip” filmmakers, and less attuned to what makes a film noir really work. The fragments of meaning and truth Huack gives us in Too Late seem less important when the movie’s soap-opera-like plot comes fully into the light, and suddenly, “playing around with narrative” feels less like a literary device and more like an amateurish gimmick.

.jpg)